The One and Only ‘Booger’ Was Among History’s Best Rodeo Performers

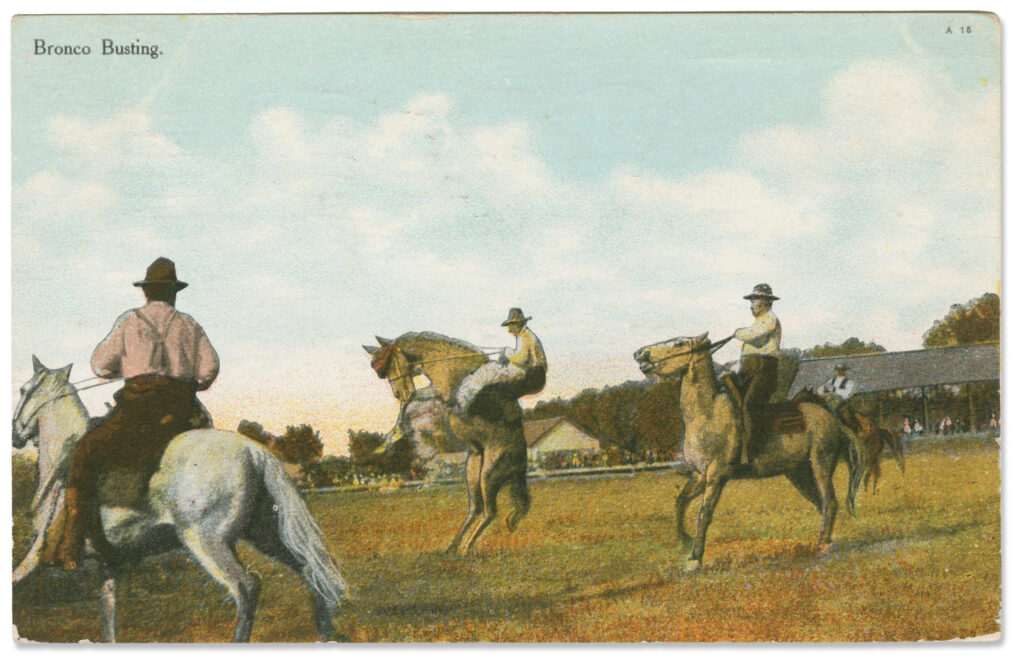

The horse was once as essential to Western life as the six-gun, and breaking horses was once a necessary skill, even a business for a few tough, enterprising souls. Eventually it became a competitive rodeo event in which working cowboys pitted their skills against wild horses—and each other. The king of the Texas broncobusters was a diminutive fellow named Samuel Privett Jr., known to history as “Booger Red.” While certain details and dates of his life differ due to faulty memories and inconsistent records, the central narrative of his life is consistent—and, oh, what a life he led!

Samuel Thomas Privett Jr. was born on the TP Ranch in Williamson County, Texas, on Dec. 29, 1858—or maybe it was 1862, or 1864. Again, the records vary. He grew up on ranches, riding and roping. As a boy of barely 12 Sam was already breaking horses, his conspicuous shock of red hair landing him notice as “that redheaded bronc-riding kid.” He was 13, or perhaps 15, when a tragic event led to his lifelong nickname, “Booger Red.” He and a pal were fooling around with a homemade firework, having packed a stump with gunpowder, when it blew up prematurely, killing the friend and disfiguring Sam’s face. On catching sight of “Red” after the accident, one boy commented how “boogered up” his face was.

Amusing moniker aside, Red’s injuries were anything but humorous. The blast had scorched off his eyebrows and part of his nose. His eyelids were reduced to slits, and he lost most of the sight in one eye. It took six months and multiple skin grafts to salvage what remained of his face. Anyone else would have retreated into seclusion, but Red was made of sterner stuff. For the rest of his life, while he was understandably camera shy and wore a wide-brimmed hat pulled low over his face, he embraced the nickname and even joked about it. His boogered-up face was just one of the curves life threw at him. The next curve was harder. By his mid-teens both of his parents had died, forcing the orphan to strike out on his own.

On his bowed legs Red stood about 5 feet 5 inches, and he weighed little more than 150 pounds soaking wet. He was also soft-spoken, leading many to underestimate him. Those who had seen him in the saddle knew better, and Red found steady work breaking horses for ranchers. With his earnings he bought a wagon yard and stable in San Angelo, though he “officed” out of a pool room in a saloon. He also broke horses for the U.S. Army, which for decades to come would mount its cavalry on animals rather than motor vehicles. As for pay, the Army offered Red a choice: $50 a month, or $1 a horse. He took the second offer, and by the end of his first day was reportedly owed $75. The Army quickly rescinded its offer. Anyway, Red could make more freelancing for ranchers.

He soon found an even more lucrative and entertaining way of making a living—riding competitively in small-town fairs and stock shows. Ranchers and cattlemen brought their wildest horses to such events and offered prize money to anyone who could gentle them. There were no arenas in those early days, just a patch of open prairie with poles stuck in the ground and rope strung between them. Spectators stood or sat in buggies or on camp stools. The only “box seats” were the saddles of those watching from horseback. Bets laid on both horse and rider were collected only when a rider went sailing or a horse quit bucking. The odds either way were about even, unless Booger Red was aboard. He took on any animals, even those with reputations as man-killers. Mounting was a challenge in itself. As there were no chutes—the side-opening chute came along years later—a rider had to get on while fellow cowboys held the animal by its ears and covered its eyes. As soon as the rider was in the saddle, the others let go and scattered. Red rode one notorious bronc that pitched and bucked across several acres before finally coming to a halt, its sides heaving, its head low and mouth flecked with foam. Rider and horse were equally exhausted, but Red walked away with a nice purse.

(History of America (Alamy Stock Photo))

These impromptu, open-air gatherings eventually morphed into organized rodeos that charged admission and programmed the various events—bronc riding (saddle and bareback), steer wrestling (aka bulldogging), roping and trick riding. As the frontier faded into history, rodeos and Wild West shows sprang up to keep the memory of the old days alive. Such shows were a combination of nostalgia and genuine cowboy skills.

Starting a Family and a Business

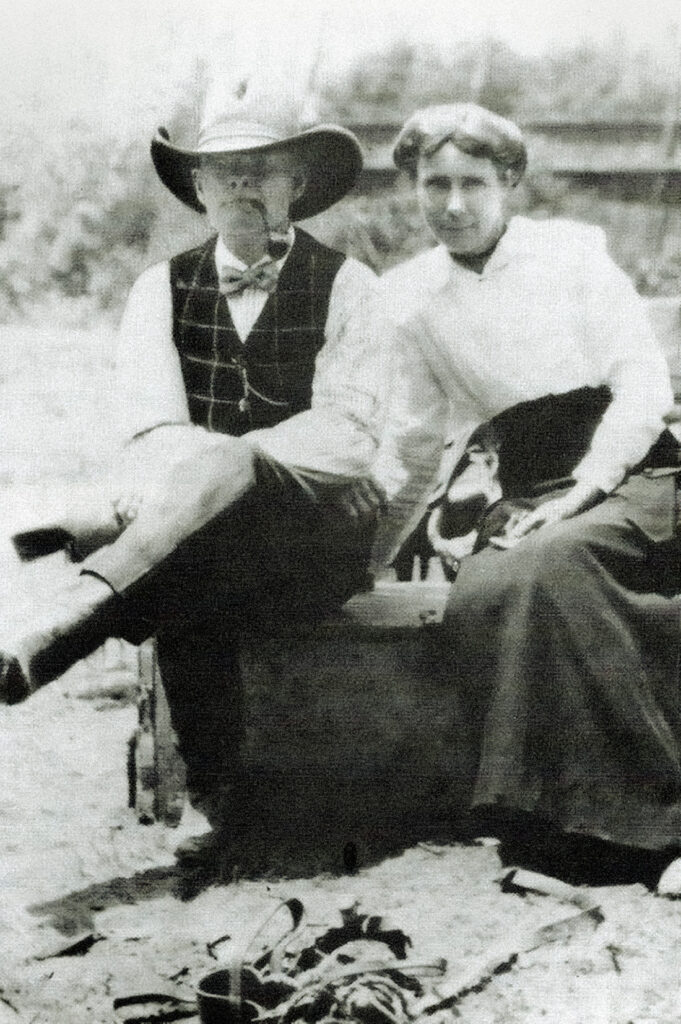

In 1895 Booger Red found love. He was 37 (more or less), while Mary Frances “Mollie” Webb was, by one account, just 15 years old. Sources vary on how old each was and when exactly they married, but by any reckoning it was a May-December romance. Red met “Mollie” at a church singalong, for which he provided musical accompaniment on the harmonica. At the time she hailed from the little town of Bronte, in Coke County, and was the prettiest thing he had ever seen. To his surprise she also was taken with him, and to his further delight he learned she was an accomplished rider. Apparently, her parents had no problem with their teen daughter dating a man more than twice her age, and the couple tied the knot before the year was out.

They settled down in San Angelo, where Red continued to operate his wagon yard and stable and break horses on the side. They ultimately had seven children, starting with Roy in 1896, followed by Ella, the twins, Tommy, Bill and, finally, Alta in 1909. Only one of the twins, Luther, survived. The other was buried as “infant daughter.” None of the children made it past the 11th grade in school. Despite their ever-expanding parental responsibilities, Red and Mollie resolved to start a new business. (The settled life had never been for him, and Mollie was game for anything.) Selling the wagon yard and stable, Red used the money to start Booger Red’s Wild West & Vaudeville Show. By 1907 he had the operation off the ground.

(Richard Selcer Collection)

By the turn of the century Wild West shows were all the rage, Buffalo Bill’s representing the gold standard. But there was always room for another. People couldn’t get enough of seeing the Old West recreated in arenas. Mollie sewed costumes for the show, and she and the kids were part of the act. Mollie performed as a trick rider. Ella, the oldest, did a riding and roping act. Tommy was a “fancy roper,” good enough to eventually land a steady gig with the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Bill was a born jockey in the saddle. But the main attraction was Booger Red, bronc rider of all bronc riders, who rode any horse brought to him, as well as a few steers and a bull he named “Andy.” Red bragged he could ride anything on four legs and made a standing offer of $100 to anyone who could bring him a horse able to throw him. Though many took him up on that offer, Red reportedly never had to pay off.

The co-star of the show was Red’s horse, Montana Gyp, who had once belonged to a Montana showman who brought Gyp to San Angelo and offered to pay $1,500 to anyone who could stay on his “outlaw horse.” Red accepted the bet, rode Gyp to a standstill, then used the prize money to buy him. Rider and horse were inseparable for the next 23 years, as much a team as Roy Rogers and Trigger or Gene Autry and Champion.

Montana Gyp was more than a mere show pony, as Booger Red’s Wild West traveled between towns not by special train but by horseback and wagon. When not on tour, the Privetts wintered on a ranch north of San Angelo. By 1915 they were making regular appearances in Oklahoma, so Red sold their San Angelo spread and bought a ranch near Miami, Okla., at which the family could winter and recoup. Around 1920, when the show got to be too much of a business, Red sold out to the Miller Bros. 101 Ranch Real Wild West. For the next several seasons he and the kids performed at others’ shows—including the Ringling Bros., Al G. Barnes and Hagenbeck-Wallace Bros. circuses—while Mollie remained on the ranch. The middle-aged Red remained on the circus and rodeo circuit a few more years, faithfully sending his winnings home to Mollie, who had taken to calling him “Old Man.”

Eventually, even those events became a chore. The time spent away from home, the endless succession of performances, the gypsylike life—all became too much, and Red decided to retire. He had no regrets. He remained at the top of his game, and it gave him pleasure and paid the bills. But he was pushing 60, which made him practically prehistoric among rodeo performers. He had experienced the bright lights and big times, performing at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, in Chicago, as well as the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition, in San Francisco, at which he was named the “World Champion Bronc Rider.” There were no more worlds to conquer.

(Courtesy West Texas Collection, Angelo State University)

A forgotten figure from Red’s life story is the young protégé he mentored, known professionally as Booger Red Jr. Junior was no relation; it was Privett who gave him that handle. “That’s the only kid I’ve ever seen that has the makin’s of as ugly a man as I,” Red declared the first time he laid eyes on the young man. Junior, whose real name has been lost to time, was described as an “all-round product of the Texas range,” just like his mentor. A top rider in his own right, junior appeared on numerous programs with the original Booger.

One of Red’s favorite stops in later years was Fort Worth, where he regularly appeared at the annual Fat Stock Show. In March 1916 he came to town by train for the show and left his grip in the baggage room at the Santa Fe depot. When the attendant offered him a check, he said he didn’t need one. “This grip belongs to the ugliest man in Texas—in the world,” Red replied. “If anybody uglier than ‘Booger Red,’ of Tom Green County, shows up, give him the grip. He’s welcome to it.”

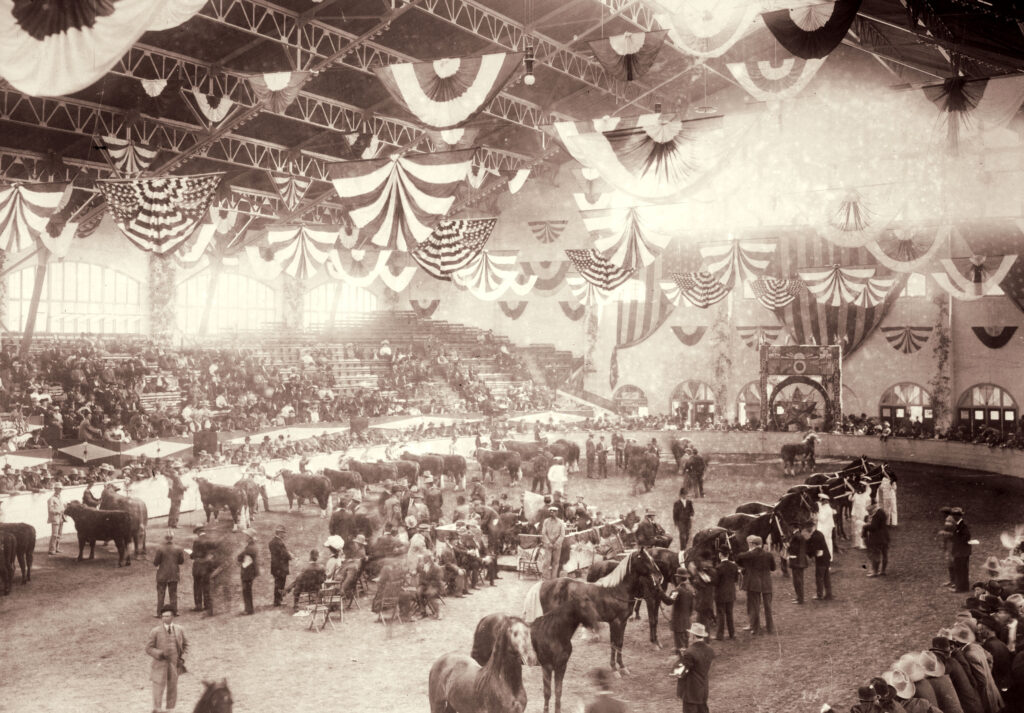

In 1918, when the show promoters added a rodeo to the Fat Stock Show, Red signed on as a competitor. Held in the Grand Coliseum (later renamed the Cowtown Coliseum), it was the world’s first indoor rodeo. A lot had changed in the intervening years. Red recalled having ridden broncs on a nearby patch of prairie cordoned off by rope. While spectators then weren’t expected to pay a dime to watch cowboys compete, thousands now crowded into the coliseum, paying 25 cents a head. Though by far the oldest entrant competing for the $3,000 in prize money, Red could still outride all challengers. For the next few years he returned to compete. While he loved the attention, however, he retained his aversion to being photographed or filmed. It was the dawn of Hollywood, and motion picture companies regularly came calling, hoping to make a star of Booger Red. For the most part he managed to dodge their cameras.

“Give us Booger Red!”

Red was remarkable for more than just his advanced years and scarred visage. For one, he never touched liquor, reportedly to keep a promise made to his mother on her deathbed. A rodeo performer who didn’t drink was akin to a dog that doesn’t bark. Keeping his promise wasn’t a simple matter of abstinence. There was little else besides liquor to drink on the ranching frontier, while rodeo performers used liquor to both pass the time and ease aches and pains. (No record remains of whether Red’s vow covered beer.) The bronc rider was not completely tamed and curried, however. Red smoked a corncob pipe, chewed tobacco and boasted an ability to spit a stream of tobacco juice with accuracy and distance.

No matter how good one is in the saddle, riding half-wild horses (and steers) is dangerous work. Red suffered his share of broken bones over the years. At one Wild West performance a bronc struck a corral post and fell on Red, breaking his leg. But the showman refused to crawl off. He remained in the saddle when the horse regained its feet. No injury ever kept him from riding. That toughness helps explain why he was so admired by fellow cowboys. He was the real McCoy, not some fancy-pants trick rider.

Though Red officially retired in 1924, he couldn’t stay away from the arena. Like an actor returning to the footlights or a jock drawn to the gym, he came back to Fort Worth that year for the annual Fat Stock Show & Rodeo, but as a spectator. His performing days were behind him, or so he thought as he sat in the stands watching the Monday matinee rodeo that March 10. He had a nondescript cap pulled low over his face and hoped no one would recognize him. All was working to plan until a “hell pitchin’ hoss” named Romeo broke away from handlers, electrifying the sparse crowd. “Give us Booger Red!” the spectators began chanting. A woman in the stands beside Red suddenly stood, pointed at him and shouted, “Here he is!” The crowd went wild. Moments later, his blood racing, the nearly bald old man made his way down the coliseum steps to the arena floor, swapping his cap for a Stetson before climbing aboard the outlaw horse. Romeo promptly broke across the arena, Red hanging on with one hand and waving the hat with the other. Soaking in the smell of the horse and roar of the adoring crowd, he tipped and pivoted with each buck and twist. The ride ended with him firmly in the saddle, keeping alive the legend of never having been thrown.

Not Forgotten

Just two weeks later, back home in his own bed, Samuel “Booger Red” Privett died of Bright’s disease, the same ailment that had taken his father. He was 66 years old—or maybe 62, or even 60. His last word to family members gathered bedside began with, “Boys, I’m leaving it with you,” and ended with, “Have all the fun you can while you live, for when you are dead, you are a long time dead.” Red was buried in the Grand Army of the Republic Cemetery in Miami, Okla. (According to family lore, Mollie couldn’t afford a headstone, so his grave remained unmarked until Ella had a slab installed in 1980.) Mollie lived another 45 years, dying on Sept. 26, 1969.

( Library of Congress)

Gone but not forgotten, Booger Red lived on in Western lore. For decades afterward old-timers related stories of his exploits. It seems everyone in Fort Worth was in the stands for his last ride in 1924. Renowned Texas poet Whitney Montgomery wrote verses about the celebrated bronc rider, and Red was written up in a 1944 issue of the Southwest Review literary journal, a story picked up by Reader’s Digest. Famed folklorist J. Frank Dobie kept his story alive, and 70 years after Red’s death Fort Worth journalists were relating the story of “Booger Red’s Last Ride” to new audiences. The legendary bronc rider was inducted into Oklahoma City’s National Rodeo Hall of Fame in 1975, and in 1991 the cumulative years of interest finally prompted a biography. Red and Mollie’s last surviving child, Alta, was still living when her father’s biographer came calling. But Charlsie Poe ran into familiar obstacles faced by all biographers—namely, fallible memories, inflated legends and contradictory sources.

Visitors to the historic Fort Worth Stockyards may recognize the name Booger Red, for when proprietors of the 1907 Stockyards Hotel remodeled the place in 1984, they named its restaurant-bar Booger Red’s Saloon. (Never mind the irony of naming a saloon after a man who never drank.) Patrons don’t belly up to the bar for their “tanglefoot”; they climb up on saddle-topped stools, often asking, “Who or what the heck is ‘Booger Red’? Is he a real person?” The answer, of course, is yes, he was a real person, a genuine cowboy and rodeo performer who made his last ride only steps down the road in Fort Worth. Half a block away, at 121 E. Exchange Ave., is the Cowtown Coliseum, looking much as it did a century ago when Booger Red performed for thousands of cheering rodeo fans.

As one fan summed it up years before, “There will only be one Booger Red.”

Richard Selcer is a frequent contributor to Wild West who has written 11 books about his hometown of Fort Worth, Texas. His primary sources for the article were the privately printed 1991 book Booger Red: World Champion Cowboy, by Charlsie Poe, and articles from early Texas newspapers.

Originally published in the Spring 2024 issue of Wild West.