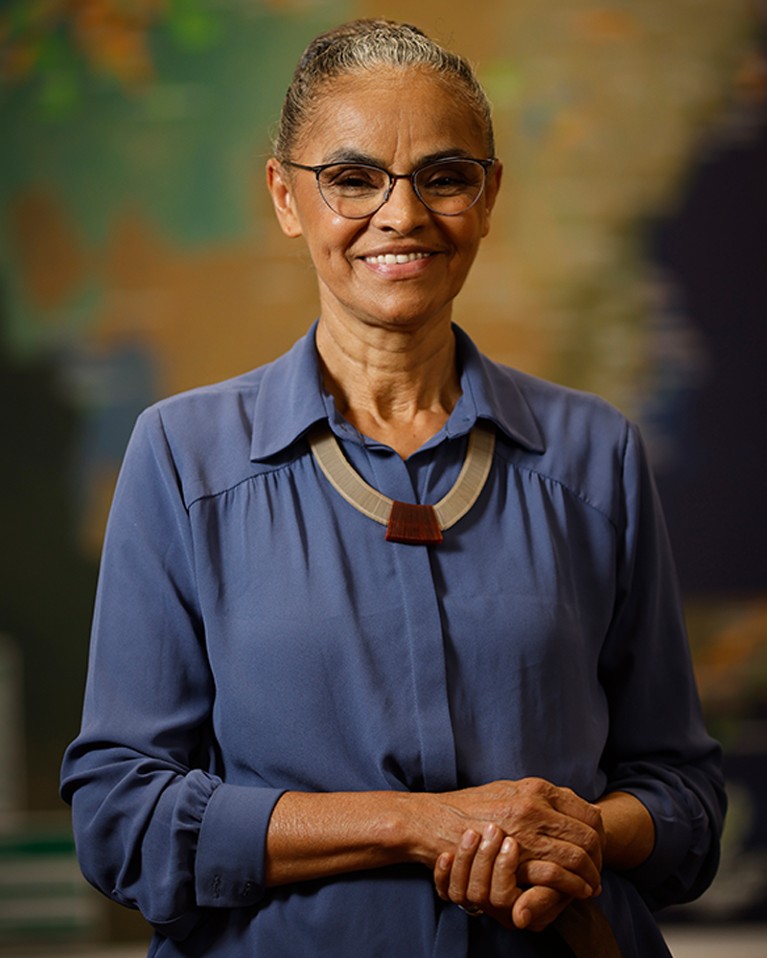

the Brazilian politician who turned the tide on deforestation

Credit: Adriano Machado for Nature

This story is part of Nature’s 10, an annual list compiled by Nature’s editors exploring key developments in science and the individuals who contributed to them.

In a year that brought unrelenting bad environmental news, with record global warming, searing heatwaves and fires, Marina Silva delivered a hopeful message on 3 August. Brazil’s environment and climate-change minister announced that there had been a 43% drop in deforestation alerts on the basis of satellite images of the Amazon rainforest between January and July 2023, compared with the same period in 2022. This was a sharp shift from the previous four years, which had seen a marked rise in such alerts.

Nature’s 10: read the 2023 list

The turnaround for environmental protections in Brazil started on 1 January, when Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva took office as president and Marina Silva assumed her current role. It’s her second time heading the ministry of the environment and climate change, which she ran previously between 2003 and 2008, during Lula da Silva’s first and second presidencies.

During her first time in office, Marina Silva tackled rampant forest-clearing activities by leading the development of the Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Legal Amazon (PPCDAm) — a programme that achieved an 83% decrease in deforestation between 2004 and 2012 in the Brazilian Amazon.

But many of the protections she helped to put in place were dismantled by the government of Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil’s president from 2019 to 2022. During his term, the government issued 40% fewer fines for environmental crimes, and logging in the Amazon increased by about 60% compared with the four previous years.

Silva and her team started this year, she says, “with the tough mission to reconstruct what had been dismantled and, at the same time, create new results for environmental policy”.

From an early age, Silva has embraced difficult challenges. She was born in 1958 in Rio Branco, Brazil, in the heart of the Amazon region. Coming from a poor family of 11 children (3 of whom died young), Silva started work at an early age along with her siblings, extracting latex from rubber trees. She wanted to be a nun and didn’t learn to read or write until she was a teenager.

Silva met environmental activist Chico Mendes (who was killed in 1988 by a rancher) on a course in rural leadership in the mid-1970s and started her career in environmental activism, which led eventually to politics. In 1994, she became Brazil’s youngest elected senator at 35 years old.

In her current role, Silva is not always in alignment with the current government, says Pedro Jacobi, an environmental-governance researcher at the University of São Paulo, Brazil. The Lula da Silva government intends to increase drilling for oil and gas — including at the mouth of the Amazon River, says Jacobi. So the environment ministry is “walking on thin ice all the time”, he says.

But in terms of controlling and preventing deforestation, Brazil is doing its homework, says Natalie Unterstell, president of the Talanoa Institute, a climate-policy organization based in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. “Marina Silva’s leadership on this agenda is very important and she is doing an extraordinary job,” says Unterstell.

One key achievement was launching a revamped version, on 5 June, of the PPCDAm programme to protect the Amazon, which the Bolsonaro administration had shut down. Silva also reinstated support for policing the region to enforce environmental regulations. And it was soon clear that the policies were working. Between January and July, the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) issued 147% more fines for environmental crimes than it had averaged during similar months between 2019 and 2022.

According to data from Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE), deforestation in the Amazon from August 2022 to July 2023 is estimated to be 22% below what it was in the previous 12 months. The rate is the lowest since 2018, but is about twice that of 2012, when deforestation was the lowest since INPE satellites began taking measurements in 1988.

Silva says one of the keys reasons why environmental protections are working is that a wide swathe of the government is promoting this agenda. “What fills me with joy,” she says, “is to see at work a concept that is very dear to me — that environmental policy should not be restricted to only one sector, but traverse all ministries.”

But ending deforestation is not enough. “If countries do not reduce their CO2 emissions from fossil fuels, forests run the risk of being destroyed due to climate change, in the same way. So we need a civilizational change, a change in our ways of life.”

She likens herself to a strong fibre from an Amazonian tree, which is used to bind wood to create rafts. “This is how I see my work,” she says, “bringing together those who are available and whatever is necessary to form a support surface in the challenging journeys of our time.”