Watching the “King of the Hill” Revival from Texas

I came to “King of the Hill” late, during the COVID pandemic. The animated hit co-created by Mike Judge ran for thirteen seasons starting in the late nineties. I’d avoided it then, largely because Judge’s previous show, “Beavis and Butt-Head,” had left me feeling squeamish—those pervy stoner chuckles; the word “bunghole”—and also embarrassed that I couldn’t hang. Watching “King of the Hill” for the first time, I was reassured to realize that the show’s repressed central character, Hank Hill, wouldn’t have been able to abide “Beavis and Butt-Head,” either. (If someone said “bunghole” in Hank’s presence, he would no doubt make one of his signature sounds, a panicked, muffled yelp: bwah!) My friends who’d watched the show when it first aired tended to relate to Hank’s son, Bobby, the show’s lazy, husky, prepubescent weirdo. But, coming to it as an adult, I found that it was Hank—rigid, rule-bound, secretly tender—with whom I felt a kinship.

“King of the Hill” had two main advantages as a pandemic companion: it was relaxing, and there was a lot of it—more than two hundred and fifty episodes. When the show first aired, critics had called it “defiantly slow” and “utterly trivial.” Amid a global pandemic, its slice-of-life portrayal of a suburban Texas neighborhood felt nourishing, a vicarious experience of the mundane dailiness that COVID had yanked away.

The king of the show is Hank Hill, and his royal domain is nothing fancy: a ranch house in the fictional town of Arlen, Texas. He has a job selling propane and propane accessories, and he gathers with his neighborhood friends in an alleyway to drink cans of Alamo beer. Hank is a decent man, driven by straightforward affinities. He loves his lawnmower, America, Troy Aikman, and Ronald Reagan. He is frequently baffled by his son, Bobby—a fan of prop comedy and pop culture, as expressive as Hank is repressed—and overwhelmed by his wife, Peggy, a substitute teacher and onetime Boggle champion with deep reserves of self-belief.

I appreciated the show for its ability to evoke a prelapsarian period when problems were small and solvable, and the ugliness of the world was held at bay. (It seems fitting that, although Bobby aged a few years through the course of the show, it ended before he fully entered puberty.) In early seasons, characters were hand-drawn over watercolor backdrops that bore a subtle luminosity. (The show switched to digital animation in Season 8.) At transitional moments, a few shots would linger on the sky over Arlen, a gradient of color suggesting the moment during a long summer evening when the glaze of humidity begins to give way to night. On Reddit, I found threads devoted to the feelings evoked by “King of the Hill” ’s skies: “like the comfort of the 90s/early 00s can’t describe it”; “Can you get nostalgia from a place you’ve never been to before?”; “late summer, school’s about to start, dinner at a steakhouse when you can smell it in the air. . . .”

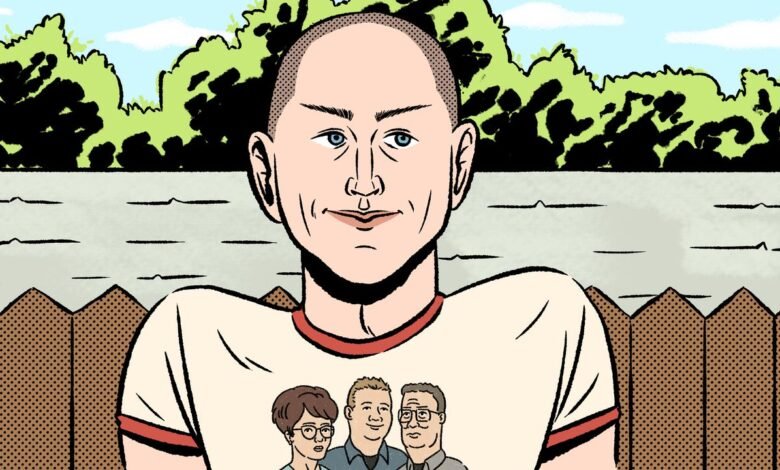

“King of the Hill” was cancelled in 2010. This week, it returns to Hulu for a ten-episode revival, set in the present day. One of the stranger conspiracies to emerge from the absurd, infuriating intervening years is the insistence by some that, owing to shadowy weather-manipulating entities, the sky has changed for the worse. “Who remembers when the sun was golden not silvery, the sky was deep rich blue, not pale milky blue, and robust gorgeous cirrus clouds were everywhere, crisply delineated in the sky; when the sky was not plagued with weird streaks that spread with horrid inevitability, blocking the sun, creating bizarre sundogs, and then turning into spitty grey unmoving cloud cover and drizzle the next day?” the author Naomi Wolf posted on X last year. Given that this is the world we live in now, I was both eager and anxious about the show’s return. How would it reconcile its easygoing charms with our current fraught reality?

“King of the Hill” premièred, on Fox, in 1997, at a time when animation was defined by antic energy and by cynicism about the American nuclear family. “The Simpsons” had been on the air for nearly a decade; “South Park” began later in 1997, and “Family Guy” two years after that. But “King of the Hill” was up to something else. The pilot episode opens with Hank and three friends standing around a vehicle with its hood popped open, gazing raptly at the engine. For more than a minute, no one says a word other than “Yep.” It was an announcement of the show’s loping Texas cadence, and also a creative risk. The show’s co-creator, Greg Daniels, fresh from “The Simpsons,” where joke density was prized, remembered “white-knuckling it” when the episode was shown to executives.

From the start, Judge claimed that “King of the Hill” was “not a political show.” It was, however, more temperamentally and aesthetically conservative than its adult-animation peers, with straightforward visual compositions and a generally realistic style. There’s little on “King of the Hill” that couldn’t have been captured with a camera. The show’s humor was grounded in a distinctly regional sensibility. (Judge has cited the New York-based observational comedy of Spike Lee’s film “Do the Right Thing” as a touchstone.) “The Simpsons” is deliberately vague about its geography, but Arlen is clearly situated in the northeastern suburbs of Dallas, where Judge lived in the late eighties and early nineties. Episodes take place at the county fair, the quarry, the Veterans of Foreign Wars clubhouse, the volunteer fire department, and Willie Nelson’s house. Reference points were Texan or Texas-adjacent; on the rare occasion that characters leave Arlen, they go see Yakov Smirnoff in Branson, Missouri, or gamble at the casinos in Hot Springs, Arkansas. This sociological fidelity extends to the show’s cars and trucks; even vehicles in the background of a scene depict specific makes and models. (Hank’s boss and Hank’s father, two of the show’s villains, drive Cadillacs, but Hank is, of course, a Ford man.)

“King of the Hill” draws humor from a suburban Texas that’s at once tradition-bound and in flux. The population of Richardson, a town on which Arlen is based, increased by some twenty per cent in the nineties, growth driven in part by members of a booming Asian community, many of whom worked in jobs in the area’s emerging technology sector. On the show, these demographic shifts are embodied by Hank’s gloating, judgmental neighbor, Kahn Souphanousinphone, a systems analyst and an aspirant to Arlen’s Laotian American élite. (In Season 6, Hank is elated when he’s invited to join the town’s exclusive Asian golf club, only to learn that his invitation is merely to reassure the P.G.A. that the club is racially diverse.)

At a time when many sitcoms were propelled by the ritual undercutting of their bumbling patriarchs, Hank Hill is allowed to be the heart of the show. Hank, voiced by Judge, speaks with a gentle, back-of-the-throat drawl and distinctive phrasings, including what one linguist characterized as a “unique voiceless labialized velar approximant”: “what” comes out as something like “hwat.” Hank is rigid and occasionally clueless, but he’s also fundamentally good-natured, and the show adopts his precept of decency. On “King of the Hill,” gay characters, or characters who dress in drag, generally aren’t played for laughs. The show’s satire was largely rooted in sincerity, and its writers weren’t afraid to wrap up an episode with an old-fashioned moral lesson. Even so, the tenderness wasn’t naïve; Hank’s belittling father, Cotton, dies unredeemed in the show’s final season, a bastard until the end.

By the time I started watching the show, I had lived in Texas for more than a decade, in a town with a population roughly the size of my suburban high school. I was as surprised as anyone to have ended up there. Growing up, I had always associated cities with energy and dynamism—weren’t they where everything interesting happened? But I soon found that I liked knowing the justice of the peace and the postmistress. I liked commiserating with my neighbor about the potholes on the street. I joined a group that rehearsed a Shakespeare play for five years and performed it in full for one night only, to an audience of our friends and neighbors. There was, apparently, something small-town in my nature—an appreciation of limits.

I lived in Marfa, an atypical Texas town, with an economy sustained by art money, tourism, and oil-and-gas wealth. What weekend visitors missed, though, is that below the touristic surface Marfa functioned very much like anywhere else in rural Texas. (In a 2002 episode of “King of the Hill,” the characters take a road trip to Marfa, in search of uncanny nighttime orbs that have been reported in the area since the late nineteenth century, long before Donald Judd dreamed of aluminum boxes.) On bad days, the lack of anonymity was claustrophobic. But, most of the time, I found it cozy to be contained in such a small world, one in a cast of characters wrangling with the drama of the week: the dust storm, the exposed affair, the time a sheriff’s deputy accidentally shot himself in the hand. In a burst of civic enthusiasm, I joined the volunteer fire department and spent every Monday at the station, where my fellow-volunteers, most of them men around retirement age, sat around trading municipal gossip. The fire engines needed constant maintenance, which I had no idea how to perform. On a weekly basis, I was confronted with how little I knew about how things actually worked.

Living in a small, remote place required a mix of self-reliance and solidarity. The town seemed to run on an unspoken exchange of favors and obligations. You had to know someone to get anything done, but if you knew the right someone, you could get almost everything done. It was often exhausting, how every task had its social cost. Elsewhere in the country, tech companies were working to reduce this kind of friction. It was an annoyance, and a privilege, to be forced to live in a different way. Last year, just before I left on a reporting trip, my bed broke. I had bought it from one of those millennial furniture companies that sell flat-packed semi-custom furniture and promise free repairs. A representative optimistically informed me by e-mail that she would reach out to their “network” to find a “technician” to repair my bed within seven business days. In the next two months, she sent me a series of cheerful, useless updates: the company was “unable to locate a craftsperson with the skill set needed to perform the repair”; the company was reaching out to a “broader geographic audience”; the company was still “having a hard time locating a technician” in the area. They never found anyone; in the end, my neighbor and his son came over and fixed it.

I had moved to Marfa in 2012, just before Barack Obama won Presidio County (of which Marfa is the seat) by more than forty points. It sits in the borderlands of far West Texas, which, with a largely Mexican American population and higher rates of poverty than elsewhere in the state, was considered a stronghold for Democrats; during my early years in town, there were some races where no one even bothered to run on the Republican ticket. But through the years I watched signifiers of rurality—pickup trucks, cowboy hats, power tools—solidify their political valence. There was a meme that went around showing text superimposed over a photograph of bootprints in mud: “Daddy, how do you know these came from a Republican?” “He was wearing work boots, son.” Throughout rural Texas, local officials switched party affiliations. Nationwide, the rural-urban party gap widened substantially; increasingly, to be country was to be conservative was to be MAGA.

During its original run, “King of the Hill” wore its politics lightly. While there was little doubt that Hank voted Republican—on learning that he’s driving through Bill Clinton’s home town, Hank narrows his eyes and locks the car doors—Judge claimed that the show merely took “a populist, commonsense point of view.” The show was largely local in its preoccupations, and Hank’s conservatism was portrayed as more temperamental than political. He was averse to change and suspicious of what he saw as flashiness or indulgence (including novelty mailboxes and lawnmowers with cup holders).

Judge and Daniels have returned for the revival, now working alongside the showrunner Saladin K. Patterson. There’s been a time jump, during which the characters seem to have aged at different rates: Bobby Hill, at twenty-one, is eight years older; his parents, who were in their early forties during the original series, are now both retired. Hank and Peggy have spent the intervening years in Saudi Arabia, where Hank worked for Saudi Aramco—a propane enthusiast’s dream—and the couple lived in a hyper-American, grassy-lawned subdivision surrounded by sand dunes. This conceit allows the Hills to return to a defamiliarized Arlen, full of bike lanes, poke restaurants, all-gender bathrooms, and video doorbells. The show largely sidesteps politics to aim at easier targets, such as the boredom of retirement and the alienating effects of technology. (“Why would a doorbell need an app?” a befuddled Hank wonders.) When Hank gets agitated by all the change, he self-soothes by buying a spanner wrench. Hank and Peggy toy with the idea of returning to their gated community in Saudi Arabia. They ultimately decide against it, choosing the friction of life in Arlen over a place that felt “more Texan than Texas.”