‘The Sun had fallen to Earth’ — a survivor’s recollection of the Hiroshima bombing

By the summer of 1945, after peace was declared in Europe, Japan was the only power of the military coalition with Germany and Italy still at war. In Japan’s blockaded Home Islands, dwindling food supplies were prioritized for soldiers. Meanwhile, emperor Hirohito encouraged the country’s slowly starving civilians to gird for imminent invasion by Allied forces and to be prepared to give up their lives in the upcoming decisive battle that would determine Japan’s fate.

A five-month-long campaign of nightly US incendiary raids had reduced all but a handful of cities, in which most civilians lived, to cinders and rubble. One of the few urban areas to have escaped this storm of napalm and thermite was Hiroshima, a regional transport and manufacturing hub on the Seto Inland Sea.

Many of its 250,000 residents ascribed this run of luck to divine intervention by Buddhist or Shinto deities. But a pessimistic thread of gossip, shared in whispers and behind closed doors, posited — correctly, as it would turn out — that Hiroshima’s stay of incendiary execution was merely temporary, and in place only because the US government had something much worse in store for the city.

All hands on deck

Local authorities were not going to leave the city’s fate to chance. In late July, Hiroshima’s garrison ordered a massive municipal effort to clear areas for firebreaks in the central business district as a countermeasure to the sweeping fires that were expected once the US bombers finally got around to crossing the city off their rapidly dwindling target list.

How to avoid nuclear war in an era of AI and misinformation

In practice, this meant tearing down wooden houses and stores along designated thoroughfares and around key military and government buildings.

Providing the muscle on site were some 20,000 civilian volunteers. Most were farmers, men too old for military service and members of women’s patriotic associations. The adults were joined by Hiroshima’s cohort of 12- and 13-year-olds, born between 1 April 1932 and 31 March 1933.

During previous drives, children this young had been deemed too physically immature to join the city’s older schoolchildren, who, for nearly a year, had been toiling in area-munitions and aircraft plants, their education officially suspended. Now, however, the younger students represented a pool of workers too valuable to leave fallow any longer.

Although local school-board members and education officials had initially resisted putting their prepubescent charges in harm’s way, they eventually caved to army demands. On the morning of Monday 6 August 1945, commuters hurried into Hiroshima’s central business district along streets ringing with the high-pitched singing and call-and-response chanting of thousands of secondary-school students working on the firebreaks alongside their adult counterparts.

In the downtown district of Zakoba, some 300 first-grade students from the elite Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High were helping to clear wooden structures around city hall. That day, however, one boy was not on the job: 13-year-old Ōiwa Kōhei had woken up that morning with a stomach ache, and his mother agreed to let him stay at home.

Out of the blue

In the minutes before 8:15, observation posts in the prefecture’s eastern part began calling in reports to the regional air-defence headquarters bunker in Hiroshima Castle: two unidentified aircraft were approaching the city at high altitude. This seemed no cause for urgent alarm — B-29 aeroplanes had been flying over the city all summer, alone or in small formations, not dropping even a cigarette butt or an empty coke bottle on the way. Still, going by the standard civil-defence protocol, the intruders’ presence should have merited an air-raid warning to alert the populace and give people time to take cover — in a proper bomb shelter, or at least under a roof somewhere.

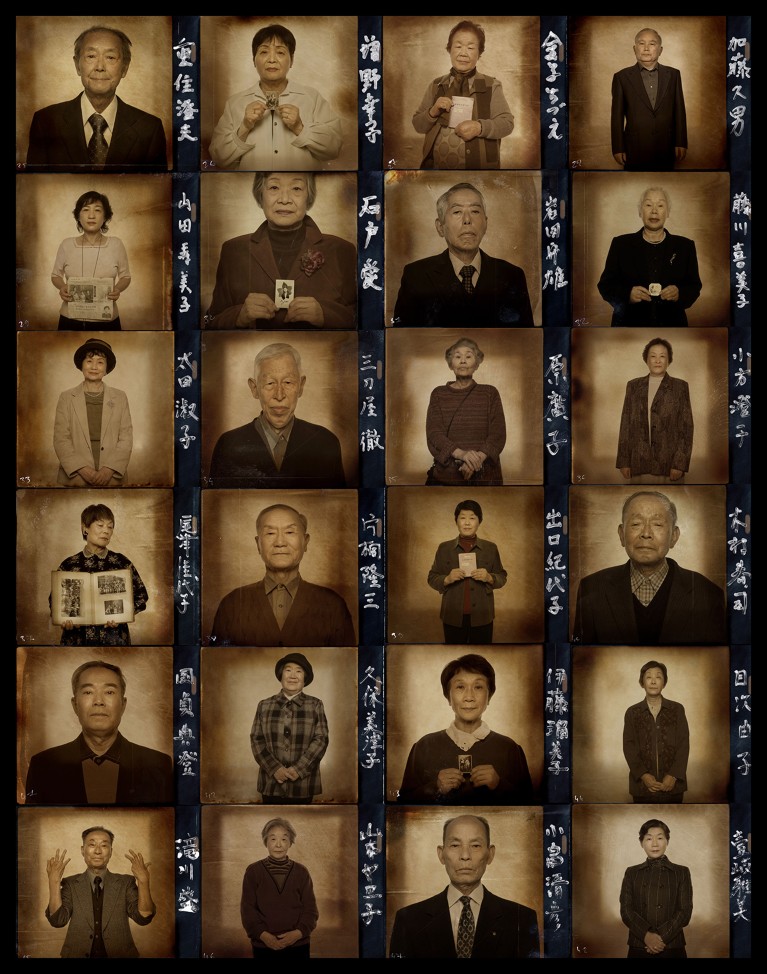

Ōiwa Kōhei was the only child his age to survive in his neighbourhood.Credit: Credit: M.G. Sheftall

Indeed, one hour earlier, sirens had sounded when a single B-29 had flown a couple of lazy circuits high over Hiroshima, and people across the city — mainly women, children and older people — had remained hidden until the all-clear signal, 30 minutes later. This time, however, when reports about the second contact began to come in, the day’s air-defence duty officer — the only bunker staff member with the authority to activate the city’s air-raid sirens — was away from his desk, consulting with colleagues at headquarters. Hiroshima’s sirens remained silent, and its residents went about their business as they would on any Monday morning.

At 8:14, the inbound aircraft abruptly went into a dive, made a full-throttled U-turn and flew away at maximum speed. People on the ground — alerted by the growl of straining engines overhead — stopped what they were doing and looked up to see three white parachutes trailing one of the bombers. Thinking that these were US crew members bailing out of a stricken aircraft, many let out cheers.

Physicists unleashed the power of the atom — but to what end?

Few people, however, had noticed a long grey cylinder — dropped by the second plane — that had already been falling for half a minute or so by the time the sound of the steeply banking aircraft reached the ground.

During a free fall of 45 seconds, this sarcophagus-like object — called Little Boy by its US makers — plummeted some 9.5 kilometres before its onboard sensors detected an altitude of 600 metres, the designated air-burst height carefully calculated by scientists at the Los Alamos laboratory in New Mexico to maximize the effect of the blast. At this point, the two halves of Little Boy’s nuclear core slammed together to form a supercritical mass of 64 kilograms of the radioactive isotope uranium-235.

Although only one kilogram of the core underwent fission before the bomb exploded, the chain reaction that took place during this blink of an eye produced a kinetic-energy pulse equivalent to 15,000 tonnes of exploding TNT.

Total devastation

To witnesses on the ground, this release of energy was initially expressed as a blinding flash of light ‘brighter than a thousand Suns’. Some 0.2 seconds later, it became a fireball — a roiling, 300-metre-wide sphere of air superheated and hyper-pressurized into ionized plasma.

This fireball assailed the crowded wooden city below with two vectors of immediate destruction. The faster of these was a burst of radiation across the electromagnetic spectrum — γ rays, X-rays, ultraviolet light, visible light and thermal rays — that reached the city at the speed of light, baking every surface it touched to temperatures ranging from 3,000 to 4,000 °C for up to eight seconds. In a combustion zone with a radius of about 1.5 kilometres from Little Boy’s hypocentre, every bit of organic matter directly exposed to this heat (twice the melting point of steel) immediately burst into flames.

Contrary to post-war US narratives about the bombing, no one caught out in the open in the combustion zone was ‘instantly vaporized’ — not even someone hypothetically standing at the hypocentre, directly under the air burst. Instead, people were essentially burnt alive for several seconds until Little Boy’s briefly supersonic shock wave front — the bomb’s second vector of fast-acting destruction — ended their agony by blowing their rapidly carbonizing bodies to pieces.

Survivors of the Hiroshima bombing, pictured 60 years later in 2005.Credit: Gerard Rancinan/Polaris/eyevine

This blast of hyper-compressed air smashed and flattened everything in the roughly 1.5-kilometre radius of total destruction. In the process, it also initiated a massive atmospheric displacement centred over the explosion’s hypocentre. After the dissipation of the shock-wave front, air from the surrounding area rushed back in to fill the temporary vacuum. This allowed thermal radiation from the still-burning fireball to promptly ignite central Hiroshima’s splintered wooden remains.

In short order, thousands of blazes merged into a fire storm so powerful that it created its own localized weather system and spread far into the parts of the city that had otherwise escaped Little Boy’s initial fury. This conflagration would rage for 24 hours and consume most of Hiroshima.

With the fireball’s brief existence having run its course and its incendiary mission accomplished, it was subsumed and sucked up and away into a skyrocketing, kilometres-high pillar of fire, smoke, dust and ash produced by the pyre of the dying city. Although this rising column of airborne debris had yet to reach its terminal altitude and flatten out into its iconic ‘mushroom cloud’ cap, tens of thousands of people already lay dead across Hiroshima, killed by the combined effects of the bomb’s electromagnetic burst and blast effect.

How a small nuclear war would transform the entire planet

Tens of thousands more would die across the city in the fire storm of 6 and 7 August. They perished in burning, crowd-crushed streets and alleys, or trapped under the wreckage of collapsed houses, or because they jumped into the city’s many waterways and drowned. By nightfall, 80,000 people had died, including almost the entirety of the firebreak work force.

In the subsequent days, weeks and months, tens of thousands of people (including first responders and carers) would die agonizing, effluvia-spewing deaths at the hands of a third, slower-acting vector of destruction: acute radiation syndrome. By the end of the year, 140,000 people had died from bomb-related causes, with another 74,000 dead in Nagasaki during the same period, because of a second atomic bomb, dropped on the city on 9 August.

Narrow escape

At the instant of Little Boy’s air burst, Ōiwa had seen a flash of light so bright that, for a few startled seconds, he thought that the Sun had fallen to Earth and landed in his mother’s flower beds. As his mind scrambled to process this thought, a whirlwind abruptly blew in all the windows in his house, lifted him from the tatami flooring and threw him across the living room and into the wall.