the real problems — and best fixes

Since taking over as the top US health official in February, Robert F. Kennedy Jr has overseen radical changes that have alarmed many public-health experts. The agency he leads announced that it would cut its workforce by 20,000, and cancelled billions of dollars in federal funding for research and public health. Earlier this month, Kennedy replaced all the members of an influential vaccine advisory committee with hand-picked ones, including some who have expressed scepticism about vaccines. His mission, he says, is to ‘Make America Healthy Again’. “We are the sickest nation in the world,” he said in March, “and we have the highest rate of chronic disease.”

Who is on RFK Jr’s new vaccine panel — and what will they do?

His diagnosis holds some truth, say public-health specialists and analysts. Relative to other similarly wealthy nations, the United States has the shortest life expectancy despite spending the most on health care. It “has the highest rates of preventable and treatable deaths”, says Reginald Williams, a health-policy specialist at the Commonwealth Fund, a think tank in New York City that publishes regular comparisons of health-care systems around the world. And researchers agree that high rates of chronic disease, including heart disease and obesity, are key contributors to Americans’ higher death rates, as Kennedy emphasizes.

But researchers say that Kennedy — widely known as RFK Jr — has mostly ignored other leading causes of death and ill health, including car accidents, drug overdoses and gun violence. In these areas, the United States “is a really clear outlier”, says Colin Angus, who studies health policy at the University of Sheffield, UK. “But, you know, I don’t see RFK talking about those things.” Kennedy has also promoted medical misinformation and conspiracy theories — particularly with regards to the safety of vaccines.

With Kennedy’s plans for US health beginning to come into focus, Nature has dug into the data to explore how unhealthy America is, how it got there and why many researchers say that some of Kennedy’s proposed solutions are misguided.

Shorter lives

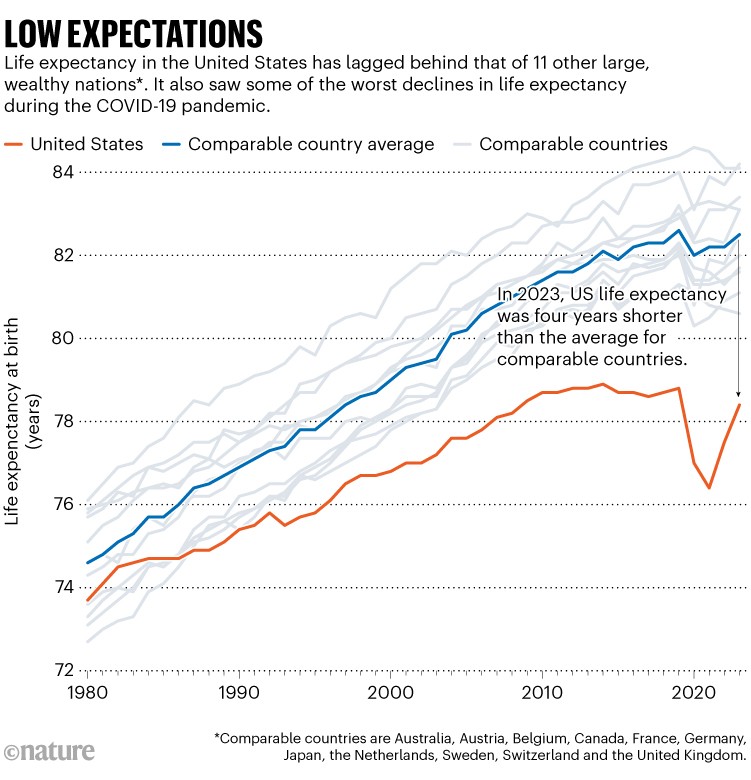

To gauge US health, life expectancy — the average number of years a person is expected to live — is a good place to start. Many analyses show that the United States has lower life expectancy than most similar nations. A comparison by KFF, a non-profit health-policy research organization based in San Francisco, California, shows that US life expectancy at birth in 2023 was 78.4 years. This is 4.1 years shorter than the average of 11 comparably large wealthy countries, including Australia, Germany, Japan and the United Kingdom (see ‘Low expectations’). “The US is just like nothing else. It’s shocking,” says Angus.

Source: Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker

People in the United States also spend fewer of their years in good shape. Healthy life expectancy — the average number of years lived in good health — was 64.4 years in 2021. This ranks below that of almost all other high-income countries, according to data from the Global Burden of Disease study1, a massive epidemiological project to measure health loss.

The gap wasn’t always so wide. Life expectancy in the United States was closer to the average for its peers around 1980 and gradually improved, according to KFF’s analyses. The gains were driven partly by a drop in smoking and increased use of cholesterol-lowering drugs known as statins, which cut deaths from cardiovascular and other chronic diseases, says Thomas Bollyky, who directs the global-health programme at the Council on Foreign Relations, a think tank headquartered in New York City.

Although that trend continued in most peer nations, improvements in life expectancy gradually slowed in the United States, plateauing around 2010. The COVID-19 pandemic temporarily widened the gap, because of higher excess mortality in the United States compared with its peers. So what’s going on?

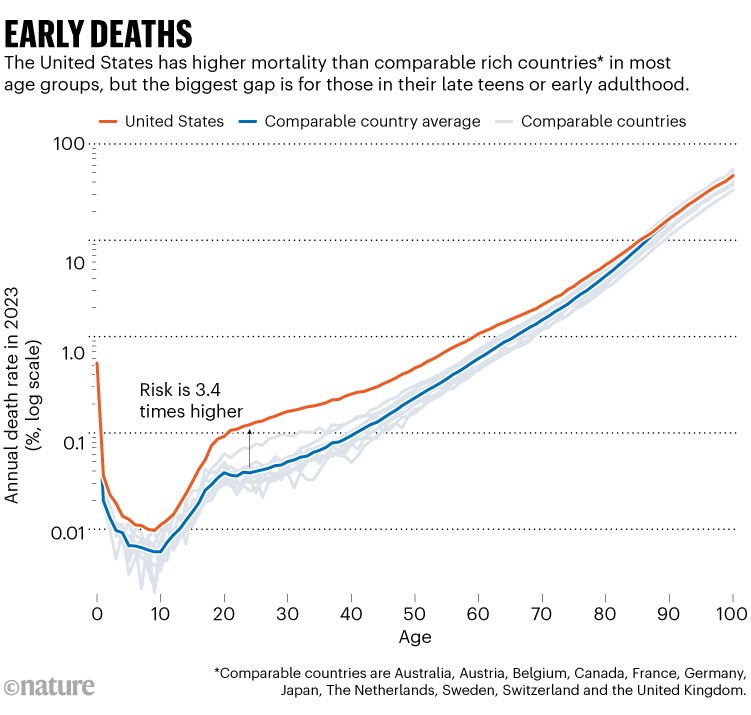

To find out, KFF researchers looked at death data across age groups. The biggest difference in death rates has been in people aged 15–49 (see ‘Early deaths’). Among these younger people, the death rate has been falling much more slowly in the United States than in peer countries — and it spiked drastically owing to COVID-19. “More people die younger,” says Lynne Cotter, a senior health-policy researcher at KFF. And because young deaths erase more years of life than do older ones, they drag down overall life expectancy.

Source: Human Mortality Database

How much does chronic disease contribute to the high US death rate? A lot. Overall, chronic conditions — heart disease, cancer, stroke and respiratory disease — take up four out of five spots on the country’s list of biggest killers. Cotter attributes about one-third of excess premature deaths in people under the age of 70 to cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease and kidney disease. “Chronic conditions certainly make up a large portion,” she says. KFF estimates that Americans are about twice as likely to die from cardiovascular disease before reaching 70 as are people in similar countries.

Exclusive: NIH to cut grants for COVID research, documents reveal

One of the biggest drivers of those deadly conditions is obesity, say researchers. As of 2022, about 42% of adults were considered obese in the United States, compared with 27% in the United Kingdom and 5.5% in Japan. Obesity increases the risks of developing diabetes, heart disease, cancer and many other conditions. “The US has, particularly around diet, obesity and overweight, adopted unhealthier lifestyles at a higher rate than our country peers,” Bollyky says.

In a May report2, the Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) Commission, which Kennedy leads, blamed childhood chronic disease mainly on ultra-processed foods, excessive screen time, lack of physical activity, exposure to chemicals and overprescription of medications. A spokesperson for the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), which Kennedy leads, did not directly address the criticisms and questions raised by sources in this article. They said that the MAHA report focuses on “a disturbing reality unfolding across the nation — the scale of the chronic disease epidemic and the institutional failures that allowed it to grow unchecked for decades”, and that the agency will next publish a report outlining policy recommendations. Americans “elected President Trump and put Kennedy in office — to Make America Healthy Again — and that’s exactly what we’re doing”, they said.

Unhealthy diets are one factor driving obesity-related chronic conditions in the United States. Credit: Derek Davis/Portland Press Herald/Getty

Research supports Kennedy’s argument that ultra-processed foods might be partly to blame for poor health. Their consumption has been linked to increased risks of obesity and some other chronic diseases, and is relatively high in the United States. Such foods comprise an estimated 58% of US daily energy intake — similar to that in the United Kingdom, but greater than the 48% in Canada and 31% in France3.

Williams says that the problems caused by chronic disease are compounded by poor health care. Compared with a group of similar high-income countries, the United States is the only one that lacks universal health-insurance coverage. “We have still 26 million people that remain uninsured,” Williams says. Lack of health insurance, high costs and other barriers prevent people from getting diagnoses and treatment early on. “And then when they do seek care, they’re at a place where their disease or needs are much higher.”

By contrast, death rates from cancer in the under 70s have remained similar in the United States and other countries, probably because of widespread cancer screening and proactive cancer care, say public-health specialists. “Cancer has moved from basically a death sentence to a manageable chronic disease,” says Williams. “So we need to have that same level of engagement around obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular care.”

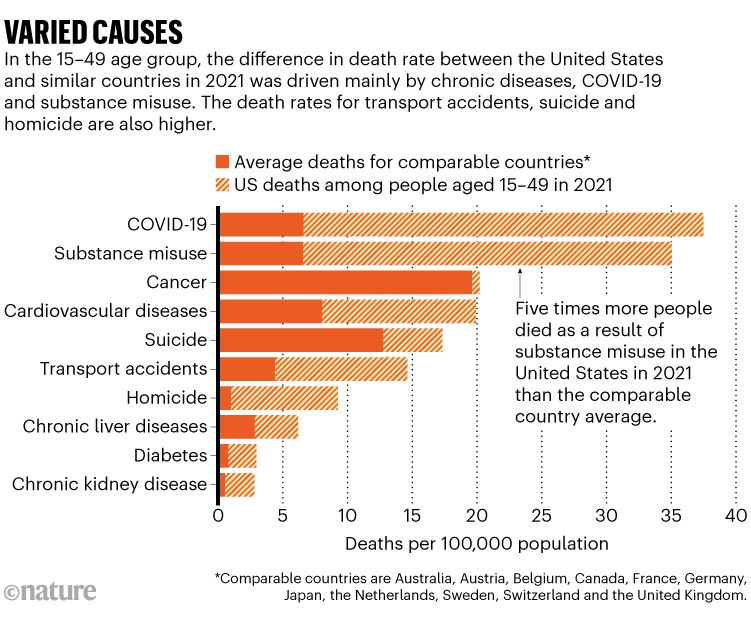

The other big contributors to lower life expectancy in the United States — and what really sets the country apart, researchers say — are high death rates from substance misuse, car accidents, suicide and homicide (see ‘Varied causes’). These tend to kill people of working age.

Source: Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker

Deaths from substance misuse are explained mainly by overdoses of synthetic opioids such as fentanyl — part of the US opioid crisis. Many Americans are killed in traffic accidents, partly because they tend to spend proportionately more time driving, and in bigger cars, than people in many other nations. “We’re a very car-centric society,” says Mary Pat Campbell, a life-insurance specialist who works at the investment-management firm Conning in Hartford, Connecticut, and blogs about mortality data. “We don’t have a lot of good mass-transit alternatives.”

Gun deaths account for about 80% of US murders and 55% of suicides. This led physician Vivek Murthy to call gun violence a public-health crisis in 2024, when he was US surgeon-general, and to highlight that it was the leading cause of death in children and adolescents. (The HHS removed this advisory from its website in March, according to news reports.) More gun deaths are suicides than homicides, says Campbell. “It gets very bleak thinking about some of these things,” she says.

It gets bleaker. All told, the death rates in working-age people mean that one 5-year-old out of every 20 — or roughly one in every school class — will die before the age of 45, according to Angus’s calculations. The comparable figure is one in 50 in the United Kingdom and one in 100 in Switzerland.

Regional differences

Although the life expectancy for the United States suggests that the country is relatively unhealthy, the average masks a more complex picture. Closer examination reveals that the figure varies drastically across the country.