Rubin Observatory Data Flood Will Let the Universe Alert Astronomers 10 Million Times a Night

Bang! Whiz! Pop! The universe is a happening place—full of exploding stars, erupting black holes, zipping asteroids, and much more. And astronomers have a brand-new, superpowerful eye with which to see the changing cosmos: the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile.

The Rubin Observatory released its first images last week, and they’re stunning—vast, glittering star fields that show off the telescope’s massive field of view and spectacularly deep vision. But two of the endeavor’s most compelling aspects are difficult to convey in any individual image, no matter how spectacular: the sheer amount of data Rubin will produce and the speed with which those data will flood into astronomers’ work.

“We can detect everything that changes, moves and appears,” says Yusra AlSayyad, an astronomer at Princeton University and Rubin’s deputy associate director for data management. Any time something happens in Rubin’s expansive view, the observatory will automatically alert scientists who may be interested in taking a closer look. The experience will be like receiving personalized notifications from the universe.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

That sounds straightforward enough—until you hear the numbers. “We’re expecting approximately 10,000 alerts per image and 10 million alerts per night,” AlSayyad continues. “It’s way too much for one person to manually sift through and filter and monitor themselves.” AlSayyad compares Rubin’s data stream to a dashcam or a video doorbell that constantly films everything in its view. “You can’t just sit there and watch it,” she says. “In order to make use of that video feed, you need data management.”

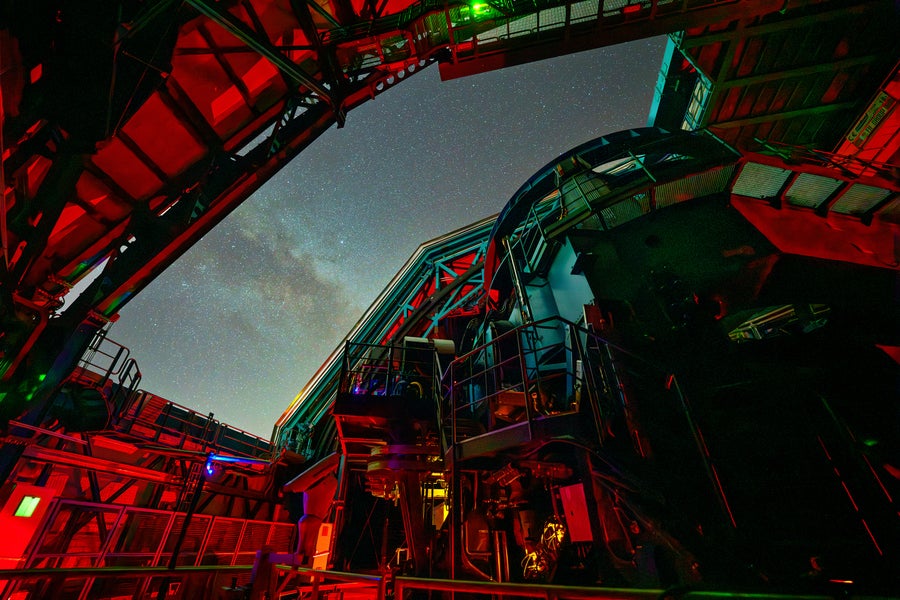

The telescope inside the dome of the NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory.

NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory/H. Stockebrand (CC BY 4.0)

For Rubin, that means building a static image of the sky—a background template, so to speak—against which any changes will be easy to spot. The telescope will construct this static view within the first year or so of regular operations.

Once the background image for a particular section of the sky is ready, the real flood will begin. As the telescope snaps its gigantic photographs, algorithms will first automatically correct for effects such as stray light from the sky and image-blurring atmospheric turbulence. Then the algorithms will compare those tweaked images with the static template, marking every little difference—an expected 10,000 in each snapshot. There will be approximately 1,000 images per night, night after night, for as long as Rubin remains in operations.

Astronomers love data, but no one has that kind of time in a day. So each individual scientist (amateurs can sign up, too) must first enroll with the Rubin Observatory’s so-called alert brokers. Users can request alerts about supernovae or asteroids, for example, then set constraints on just how interesting an event should be to trigger a notification.

Such limitations are important because, again, fielding 10 million alerts per night is an untenable prospect for anyone. “It really is a kind of overwhelming scale of data,” says Eric Bellm, an astronomer at the University of Washington and Rubin’s alert production science lead.

And that flood will continue for 10 years straight as the Rubin Observatory executes its signature project, dubbed the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST). During this period, the telescope will zip its view across the sky in a carefully choreographed dance that will ultimately produce the best high-definition movie of the heavens that humanity has ever conceived.

During its primary mission the Rubin Observatory will take about a thousand images every night, allowing it to scan the entire visible Southern Hemisphere sky every three to four nights.

NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory

Rubin’s scientists have already sketched the basic survey, says Federica Bianco, an astronomer and data scientist at the University of Delaware and deputy project scientist at the Rubin Observatory. But many details will be worked out along the way, which will let them program the telescope to adapt to the astronomical community’s interests, as well as any sudden celestial surprises.

“Ten years ago we were not really seriously thinking of gravitational-wave counterparts, which is all the rage today,” Bianco says. (These counterparts are the light-emitting sources of gravitational waves, the ripples in spacetime that scientists first measured in September 2015 using the twin Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) detectors.)

“We truly believe that LSST itself will discover new things, will transform the way in which we think about the universe,” she adds. That means making the observatory responsive to the cosmos. “If that is true, then we need to enable changes that allow us to capture these new physics, these new phenomena.”

For some science, the discoveries will be limited by whatever the sky is gracious enough to give—a star must explode for the Rubin Observatory to spot a new supernova, for example. But a particularly intriguing case comes from planetary science within our own solar system. For centuries, astronomers have snagged observations of asteroids and comets—respectively, rocky and icy objects that swarm between and around the planets as all orbit the sun.

All that effort has put more than 1.3 million asteroids in our catalogs, but astronomers expect Rubin to identify perhaps three times that many new objects—practically without trying. When the LSST survey is running at full capacity, alerts for potential newfound asteroids will be sent straight to an international group called the Minor Planet Center, which tends a database of all such space rocks.

“We just sort of sit back and these objects will be discovered and reported to us,” says Meg Schwamb, an astronomer at Queen’s University Belfast. Schwamb co-chairs the LSST Solar System Science Collaboration and has worked to estimate what the telescope will find in our cosmic neighborhood.

And because these space rocks are already out there, rattling through the solar system, Rubin will rack up discoveries quickly, Schwamb and her colleagues predict—with some 70 percent of new objects discovered during the survey’s first two years.

“That, I think, is mind-blowing. That really allows us to start being able to watch these objects,” Schwamb says. “There’s instant gratification.”

Not everything Rubin will study is so speedy and unsubtle; the observatory will also be an astonishingly powerful tool for probing the enigmatic dark matter that produces no light yet holds galaxies together and outweighs the normal, familiar matter we know in our daily lives. One way astronomers study this lightless stuff is to measure how dark matter gravitationally warps light from more distant objects. Researchers use that telltale effect to map the enigmatic substance’s distribution across the universe.

Decades ago Anthony Tyson, now an astrophysicist at the University of California Davis, wanted to do just that. “I proposed a project to [what was then] the biggest telescope, the biggest camera that was in existence, and got turned down,” he recalls. In the long run, that failed proposal sent him down the path to build his own superlative telescope, which boasts the biggest digital camera in the world, at the Rubin Observatory, where he was founding director and is now chief scientist.

In the short run, however, he took an approach that now seems prophetic. “I decided maybe I should make another application to take the same data but for a different purpose,” he says. He and his colleagues wrote up a different proposal for the same telescope, this time pitching a study of radio-bright plasma jets emanating from around the supermassive black holes at the core of galaxies. He got the observing time—as well as the warped light from invisible clumps of dark matter strewn along the telescope’s line of sight. “That was the scam,” he quips.

Now, decades later, the Rubin Observatory is opening astronomers’ eyes to a new view of the universe. And while it won’t observe radio light, it certainly will observe oodles of active galactic nuclei—by the tens of millions, in fact, repaying Tyson’s slyly earned telescope time many times over.