Reserves and Where to Find Them

Banks use central bank reserves for a multitude of purposes including making payments, managing intraday liquidity outflows, and meeting regulatory and internal liquidity requirements. Data on aggregate reserves for the U.S. banking system are readily accessible, but information on the holdings of individual banks is confidential. This makes it difficult to investigate important questions like: “Which types of banks hold reserves?” “How concentrated are they?” and “Does the distribution change over time or in response to significant events?” In this post, we summarize how non-confidential data can be used to answer these questions by providing publicly available proxies for bank-level reserves.

Who Holds Reserves?

In the U.S., central bank reserves are held by U.S. banks, domestic branches of foreign banking organizations (henceforth, branches of FBOs), and credit unions. Most reserve balances are held by U.S. banks, 57 percent of reserves on average since 2013, whereas branches of FBOs are the second-largest holders with 38 percent of reserves. Credit unions hold a small fraction of reserve balances, less than 5 percent on average; given their contribution, we do not consider them in the remainder of this post.

Bank-Level Data

Publicly available proxies for bank-specific reserves are sourced from regulatory filings. Each quarter, U.S. banks file a Call Report (forms FFIEC 031, 041, and 051) with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). The Call Report contains detailed financial information on the financial condition of banks. In the Call Report, two items on the balance sheet (Schedules RC and RC-A) contain information on reserve holdings: item 1.b. “Interest-bearing balances” (RCON/RCFD 0071); and item 4. “Balances due from Federal Reserve Banks” (RCON/RCFD 0090). However, neither item is a perfect measure of reserve balances. Interest-bearing balances (IBB) includes certificates of deposit not held for trading. Balances due from Federal Reserve Banks (Balances Due) is a more precise measure, but the field is only required for banks with total assets of $300 million or more.

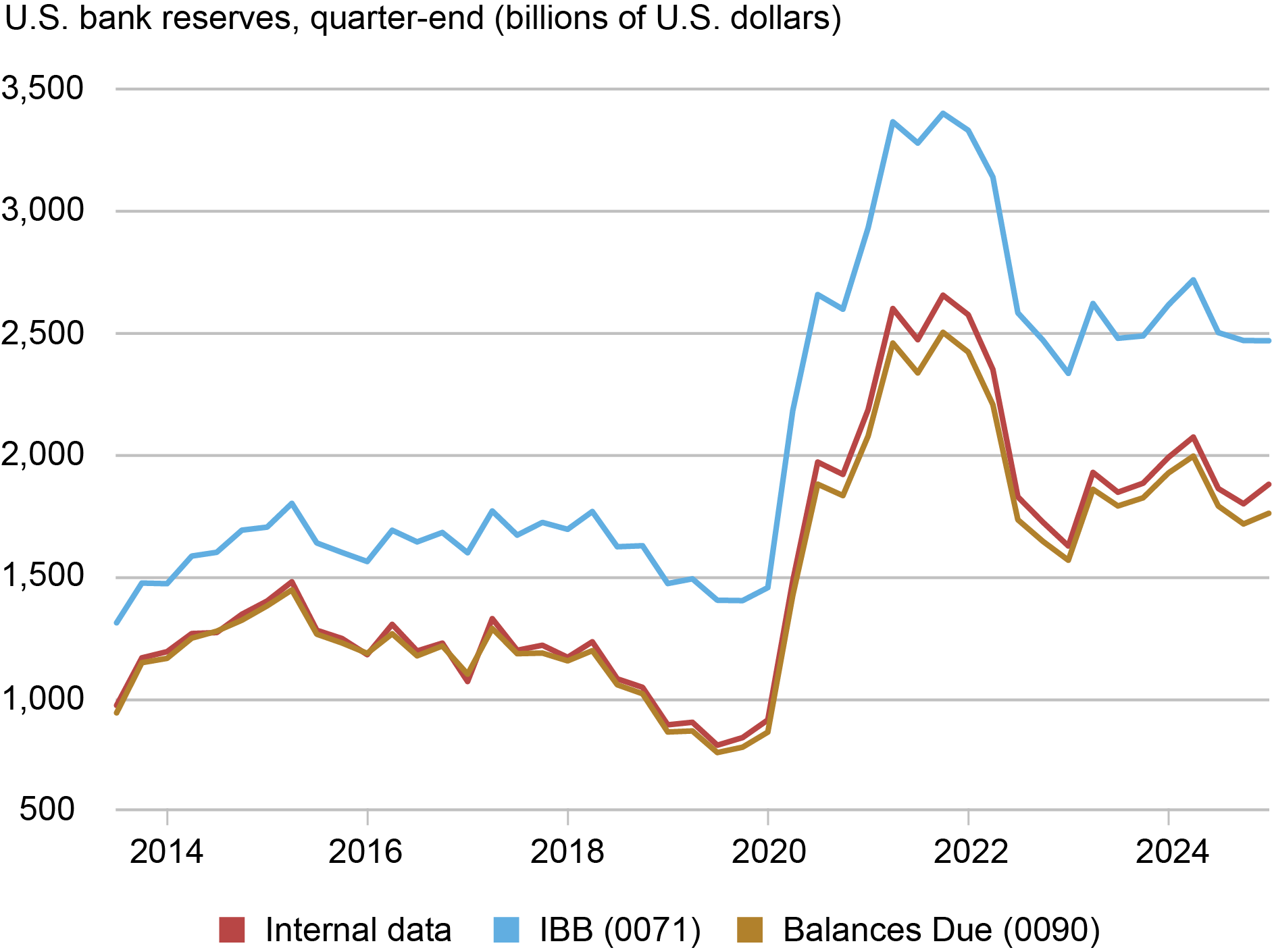

To assess which series captures overall reserves better, the chart below compares end-of-quarter aggregate reserves for U.S. banks using internal Federal Reserve data with the two series from the Call Report. The chart clearly shows that, in aggregate, Balances Due (0090) is a closer match to internal data than IBB (0071). As expected, IBB materially overestimates reserves as it includes a broader category of assets whereas Balances Due slightly underestimates aggregate reserves.

Balances Due Closely Tracks Reserves of U.S. Banks

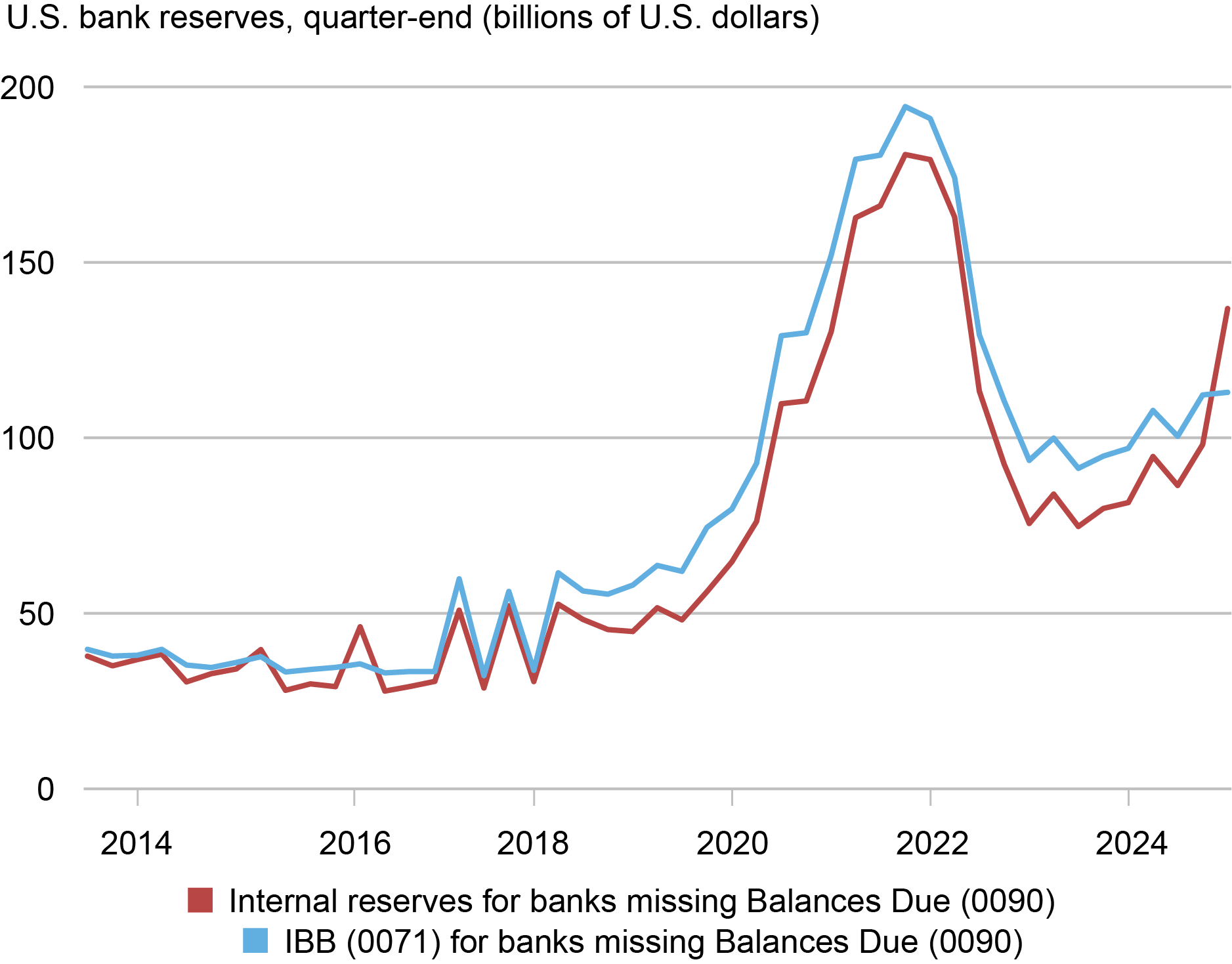

Some banks are missing the superior proxy for reserves, Balances Due, either because they have less than $300 million in assets or because the reserves are held by a correspondent bank on the bank’s behalf. The chart below illustrates that for those banks that do not report Balances Due (73 percent of banks representing 5.5 percent of bank assets), the vast majority are below the $300m cut-off.

Balances Due Is Not Available for Small U.S. Banks

As a result, in the aggregate, using 0090 will underestimate reserves held, particularly for the smallest institutions. For smaller banks that are not required to report Balances Due, IBB provides a close approximation of actual reserve holdings; for this reason, we recommend using RCON 0071 when RCON 0090 is not available (see chart below).

IBB Tends to Overestimate Reserves, but Remains a Reasonable Proxy

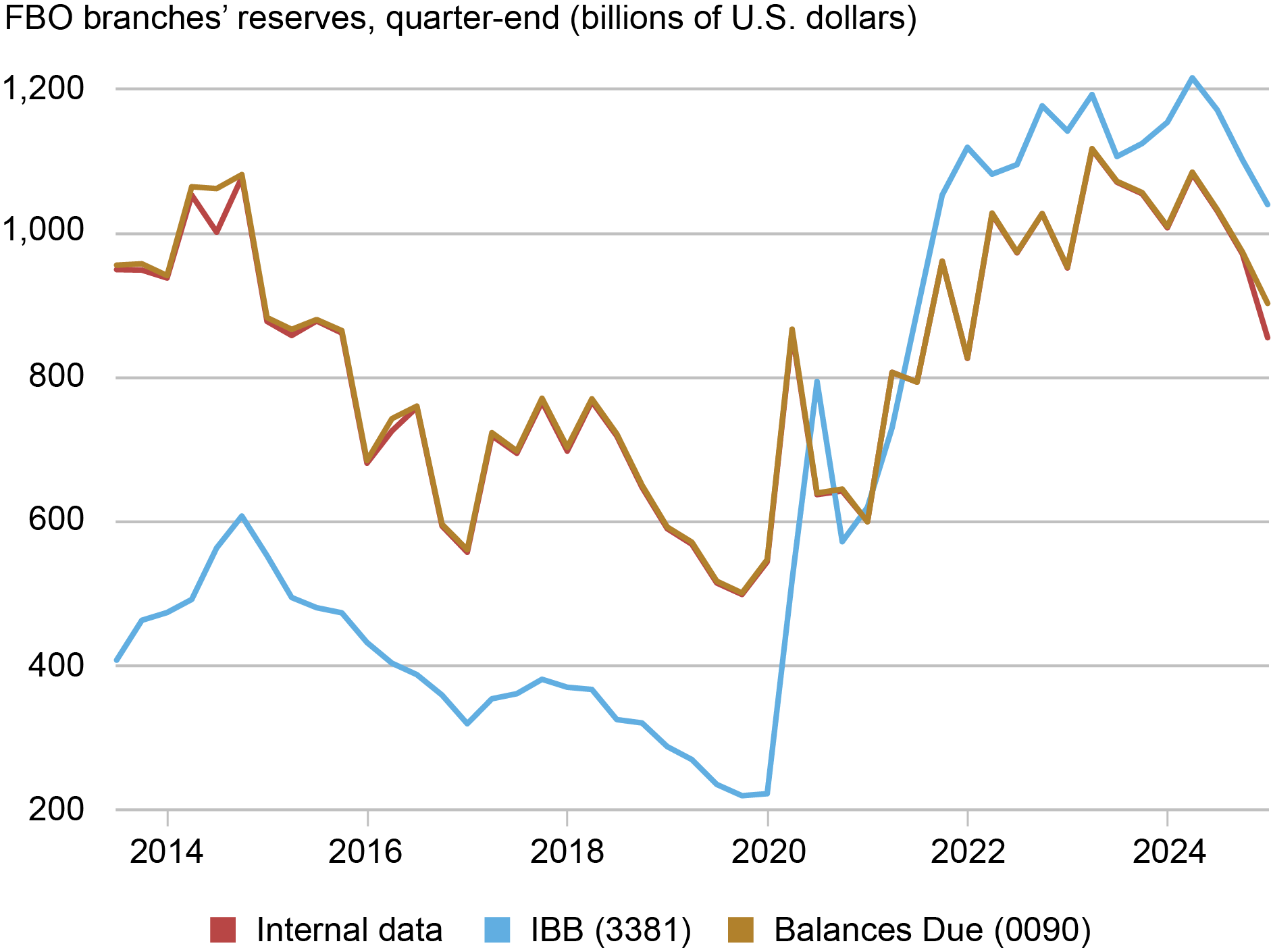

Branches of Foreign Banking Organizations

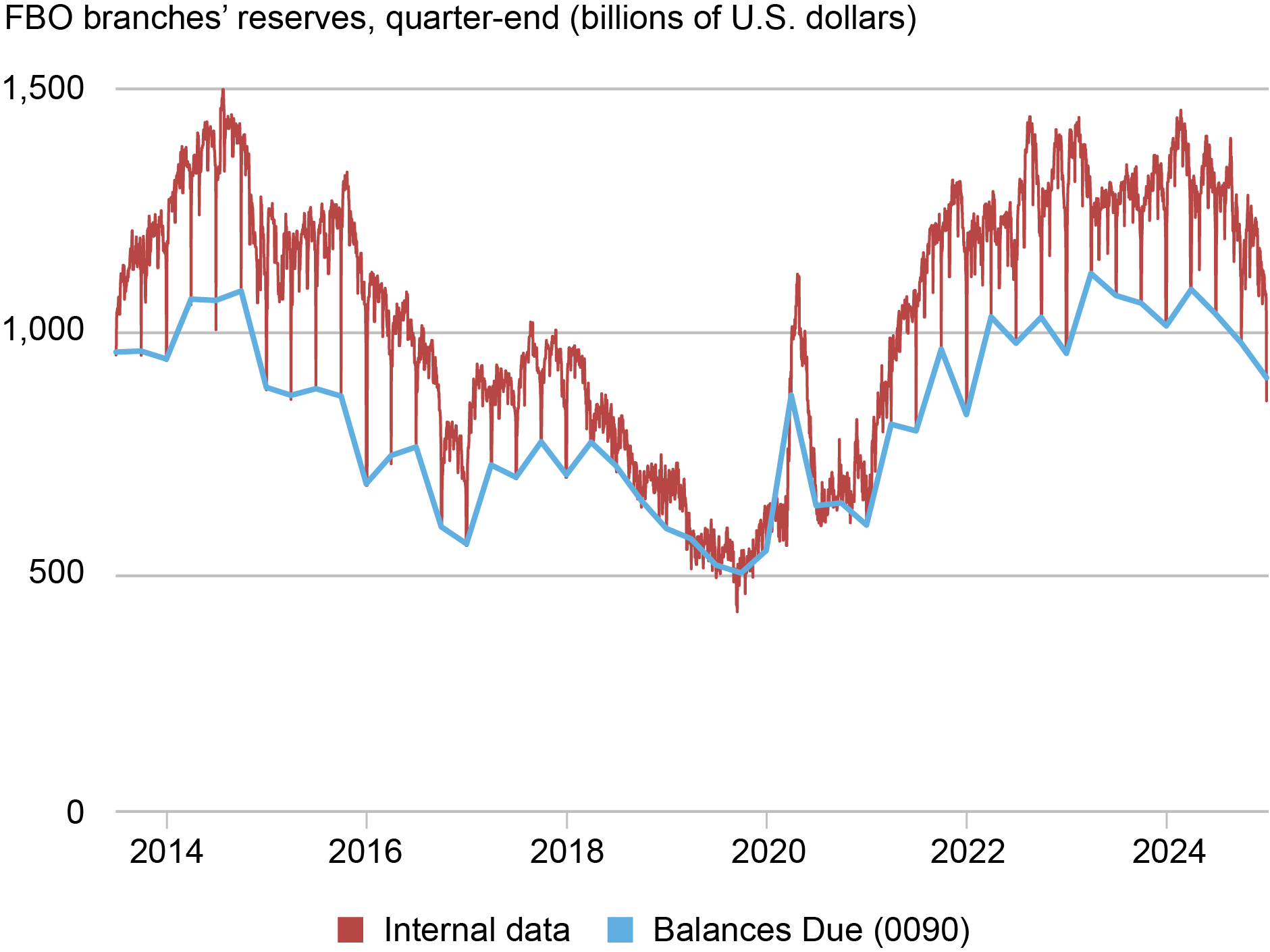

Branches of FBOs file form FFIEC 002 quarterly. Again, two items contain information on reserves, analogous to the reports for U.S. banks: item 5. “Interest-bearing balances due from depository institutions” (RCFD 3381) in Schedule K; and item 5. “Balances due from Federal Reserve Banks” (RCFD 0090) in Schedule A. Similar to U.S. banks, the chart below shows that Balances Due is a much closer match to the internal data.

Balances Due Closely Tracks Reserves of FBO Branches

One limitation of using quarterly data as a proxy is that it masks fluctuations in reserves within the quarter. This is especially pronounced for foreign banks. The chart below compares daily reserves held by branches of FBOs to the proxies generated using public filings. Reserve levels at these institutions fall at the end of the quarter, hence the public data does not reveal the average balance of reserves for these banks. On average, reserve levels at branches of FBOs are 20 percent lower at quarter end than their average level on all other days.

Reserves of FBO Branches Drop on Quarter Ends

How Does It Perform?

Using our preferred proxies for reserves—Balances Due when available and IBB when Balances Due is not reported—we can validate our proxies relative to internal data. At the aggregate level, we closely reproduce aggregate reserves held by U.S. banks and branches of FBOs. The average difference between these two series is 1.4 percent of internal reserves, reflecting the slight overestimate of reserves from smaller banks that rely on IBB as a proxy. Looking to individual banks, the median absolute error expressed as a percentage of bank assets is 3.1 percent for U.S. banks with less than $300m in assets, 0.4 percent for U.S. banks with more than $300m in assets, and 0.0002 percent for branches of FBOs.

Conclusion

This post explains how to construct quarterly, bank-specific reserve balance data from publicly available regulatory filings. This enables researchers without access to confidential reserves data to investigate questions about individual institutions’ reserve holdings and their impact on money markets, which cannot be addressed with public, aggregate reserves data. Use of public filings comes with two caveats. First, the proxy for small U.S. banks will on average overestimate their reserves, although there are small banks whose reserves are underestimated. Second, domestic branches of foreign banks tend to lower their reserves at quarter end, hence their average reserve levels over the quarter are in fact higher than what can be inferred from public data.

Gara Afonso is a financial research advisor in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Marco Cipriani is head of Money and Payments Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

JC Martinez is a research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistic’s Group.

Matthew Plosser is a financial research advisor in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Gara Afonso, Marco Cipriani, JC Martinez, and Matthew Plosser, “Reserves and Where to Find Them,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, June 23, 2025, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2025/06/reserves-and-where-to-find-them/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).