‘Love, Brooklyn’ is a Romance for a Borough in Flux

The first time I saw Love, Brooklyn, it wasn’t on a big stage with flashing cameras or red carpet energy. It was in the quiet intimacy of an advance screening, a space where the film’s moods could breathe and settle. By the time it played again, this time in front of a packed house at the BlackStar Film Festival in Philadelphia, the difference was striking. The audience was palpably leaning forward, laughing, and sighing on that summer afternoon, murmuring at all the right moments. That collective reaction underscored what had already been clear: Love, Brooklyn is a work that refuses to be contained, spilling past the edges of the screen with a pulse that feels both intimate and expansive. The film went on to win the “Favorite Feature Narrative Audience Award” at BlackStar, a recognition that felt earned in every whispered laugh and shared sigh.

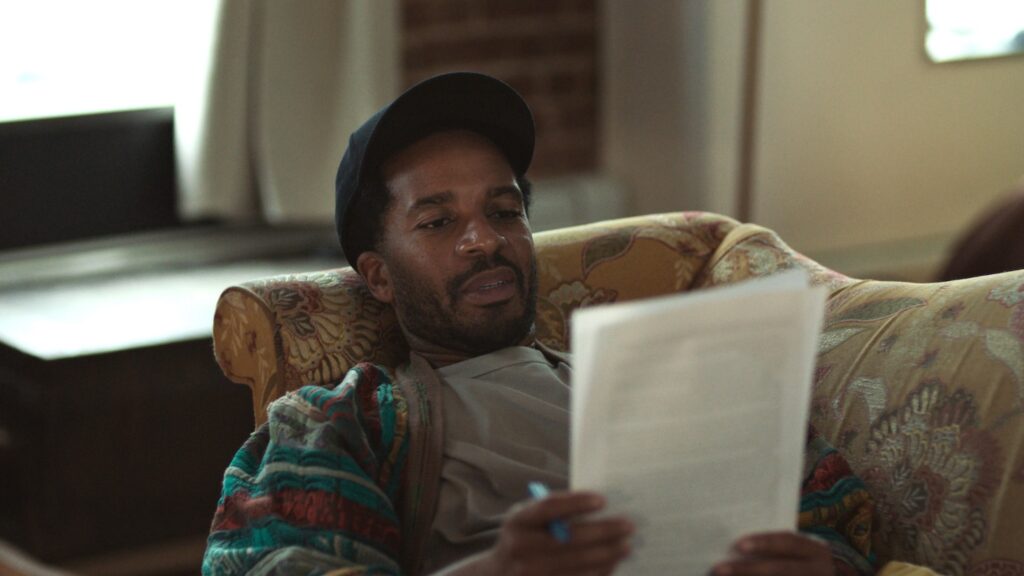

Written by Paul Zimmerman and directed by Rachael Abigail Holder, the film unfolds like a lyrical conversation with Brooklyn itself, a borough at the tipping point between belonging and displacement. At its center is Roger (André Holland), a free-spirited writer cycling through neighborhoods and emotional possibilities, anchored by two women—Casey (Nicole Beharie), his ex and a gallery owner fighting to stay rooted, and Nicole (DeWanda Wise), a recently widowed single mother whose warmth stirs something tender and real. Alongside them is Alan (Roy Wood Jr.), Roger’s blunt friend offering comic relief and clarity, and Ally (Cadence Reese), Nicole’s perceptive daughter who sees Roger more clearly than he does. The trio wrestles with love, loss, memory, and change, both personal and borough-wide, as they navigate their intertwined worlds.

The film is a love story, but not the kind that slips cleanly into a genre box. It’s part romance, part meditation on creative ambition, and part exploration of how personal and artistic lives intersect, sometimes harmoniously, sometimes with quiet destruction. The Brooklyn it captures isn’t the postcard version, but a living, breathing borough where gentrification, cultural memory, and everyday hustle complicate the path to love and fulfillment. It’s the scene in the museum that really speaks to the crux of the film—Casey and Roger discussing Henry Ossawa Tanner’s Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, and what’s lost for the sake of progress.

“I wanted to tell a story that felt honest to my lived experience,” Holder told me before the BlackStar screening. “Not just about falling in love, but about how love sits alongside work, ambition, and the compromises we make, or refuse to make.” Her characters are layered and contradictory, not because it’s fashionable to write “messy” people, but because that’s simply how humans are. “I think the audience can feel when you’re telling the truth,” she added. “Even when the truth isn’t flattering.”

Courtesy of Greenwich Entertainment

The heart of the film is André Holland, who not only delivers a quietly magnetic performance but also serves as a producer on the project. Known for his work in Moonlight and The Knick, Holland threads charisma with a simmering vulnerability, embodying a man caught between professional obligations and personal longing. “Rachael gave me a script that felt alive,” Holland said. “It wasn’t just dialogue, it was rhythm, it was breath. And that’s exciting as an actor because you’re not just delivering lines; you’re finding music in them.”

That musicality runs through the film’s visual language as well. Holder’s direction treats Brooklyn as both a setting and a character, capturing its shifting architecture, street corners, and moods with a deep affection that resists nostalgia. The cinematography, lensed by Martim Vian, balances warmth with grit, often framing moments of tenderness against the backdrop of looming change. “Brooklyn is my home. And I love it enough to tell the truth about it,” Holder said. “That means celebrating its beauty and naming the forces that threaten that beauty.”

The chemistry between the leads is undeniable, but what makes it compelling is the tension beneath their connection. This isn’t a glossy romance where every obstacle is external. Here, the conflicts are often internal, ambitions pulling in different directions, unspoken fears shaping choices. “What drew me in was that these were adults in love, with all the complexity that brings,” Holland explained. “It’s not about will-they-won’t-they in a simplistic way. It’s about: can they, given who they are and what they want?” There’s a softness to the film that allows it to let these characters grieve in a way that is not always afforded to Black folks. Working within a genre like romance, in which viewers already have their defenses down, allows the film to land in a way that lets the audience fully inhabit its intimacy.

At BlackStar, watching the film felt both personal and communal. Audience members laughed knowingly at certain lines, nodded in recognition during moments of friction, and let silence linger when the story took a breath. It’s a film that grabs your attention by earning it, not demanding it. Holder credits the festival’s energy for deepening the work. “BlackStar is such a unique space,” she said. “The audience is smart, engaged, and invested in seeing something real. That makes you want to bring your full self as a filmmaker.”

Courtesy of Greenwich Entertainment

One of the film’s most striking qualities is its refusal to tidy up life’s messes. By the end, there are no grand declarations, no sudden fixes, just a sense that these characters will keep moving forward, bruised and brightened by what they’ve shared. “That’s life,” Holder said with a smile. “We don’t get neat endings. We get moments. And if you’re lucky, you notice them.” Holland echoed the sentiment, pointing to a key scene that unfolds in near silence. “There’s this moment where nothing is said, but everything is understood,” he recalled. “Those are my favorite parts of the film. Rachael trusted the quiet.”

Watching Love, Brooklyn again at BlackStar, I found myself noticing new details, the way a glance lingered a beat too long, how a layered sound design gave the borough’s streets their own voice, the subtle shifts in body language when characters crossed emotional thresholds. This film acts as a love letter to a borough that is rarely highlighted in films about New York City, capturing the complexity and sadness in witnessing the neighborhood you once called home become unrecognizable. It’s a film that rewards rewatching, not because it’s dense with plot, but because it’s rich with human moments.

The film doesn’t just depict a place; it carries its cadence, its contradictions, and its heartbeat. The audience doesn’t just watch a love story unfold; they watch a conversation about art, ambition, and home play out in real time. In a way, the film is a reminder that love, like the borough, is never static. It changes, it challenges, and if you’re paying attention, it never fails to surprise. As Holder put it: “Love is work. It’s showing up, even when it’s not easy. And I think that’s true whether you’re talking about a relationship, your art, or the place you call home.”

The post ‘Love, Brooklyn’ is a Romance for a Borough in Flux appeared first on BKMAG.