How to spot fake scientists and stop them from publishing papers

Beatriz Ychussie’s career in mathematics seemed to be going really well. She worked at Roskilde University in Denmark where, in 2015 and 2016 alone, she published four papers on mathematical formulae for quantum particles, heat flow and geometry, and reviewed multiple manuscripts for reputable journals.

But a few years later, her run of promising studies dried up. An investigation by the publisher of three of those papers found not only that the work was flawed, but that Ychussie didn’t even exist.

How big is science’s fake-paper problem?

Her name is one of a network of 26 fictitious authors and reviewers that had infiltrated four mathematics journals belonging to the London-based publisher Springer Nature.

These sham scholars were created by a paper mill, a company that manipulates peer reviews and sells fake research papers to researchers looking to boost their profile. By inventing a stable of fake scientists, paper mills can create a ready supply of publications and favourable peer reviews, ensuring that more of the mills’ submissions get published. This tactic increases their output and credibility for paying customers.

This particular paper mill used two dozen fake authors and reviewers to publish 55 articles — one of the biggest such cases reported. After a lengthy investigation, Springer Nature, which also publishes Nature, retracted all three papers. (Nature’s news team is editorially independent of its publisher.)

Other publishers have discovered similar fakes, with fictitious reviewers being more frequent than fake authors. Researchers acknowledge that this type of fraud probably isn’t a hugely common problem, but that the true scale is unknown. “We’re just flying completely blind here,” says Reese Richardson, a metascientist at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois.

Paper mills and individuals can also impersonate real researchers, stealing their identities to make submissions seem legitimate and increase their chances of getting published.

Most publishers already check author identity before accepting submissions. Some rely on simple checks, such as whether a scientist is using an e-mail from a recognized institution. Others use several tests. Frontiers journals, for instance, cross-reference researcher records and look for previous publications. They also ask authors to confirm contributions made by others listed on the paper.

Journal targeted by paper mill still grappling with the aftermath years later

But verifying identity is difficult because journal editors, reviewers and authors typically communicate remotely through e-mail or submission systems. Scientific publishing runs mostly on trust. There are ongoing discussions about whether to adopt more stringent measures — for example, requiring use of institutional e-mails or logging in with a system that uses university credentials — and even asking for documents such as passports or driving licences.

But such identity checks risk excluding scholars who do not work at a known institution, as well as early-career researchers and individuals in low- and middle-income countries who do not have institutional e-mails, says Adya Misra, associate director of research integrity at Sage Publications in Liverpool, UK. Journal editors might not feel comfortable playing ‘immigration officers’, checking identities for every submission. “What we lack as an industry is standards on what we consider to be a verified researcher,” says Misra.

Make-believe mathematicians

In 2018, a reader spotted a pair of flawed and nearly identical papers that had been published in two mathematics journals the year before, and alerted the journal staff. The publisher of the journals, Springer Nature, discovered that both articles had used fictitious reviewers.

That was only the start. The fake reviewers had appeared as authors on earlier papers (some journals, including the two that published the flawed papers, allow authors to recommend their own peer reviewers). So once both made-up names became published authors, they began to be repeatedly suggested for reviewing.

Between 2013 and 2020, the paper mill published 55 papers with the help of 13 fictitious reviewers and 13 fake authors, who were supposedly based all over the world.

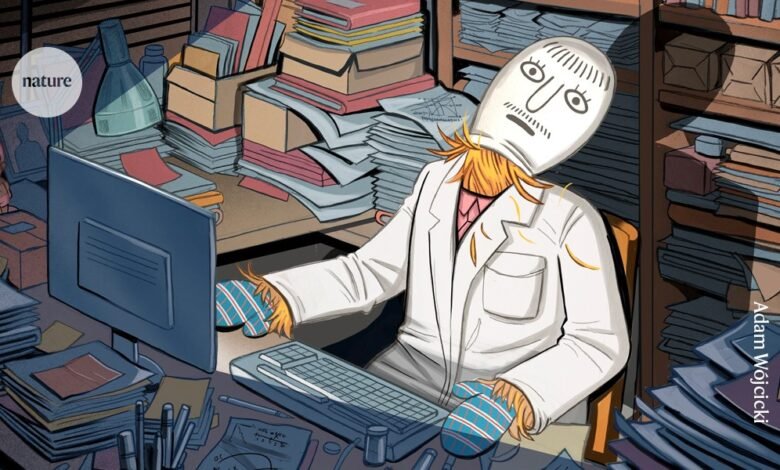

Illustration by Adam Wójcicki

Most of those fake authors appeared on only one article, but were suggested as reviewers 68 times. The other 13 fake personas had no publication history and were invited to review 25 times. When Springer Nature contacted the institutions that supposedly employed the researchers, those universities confirmed that no such people had ever been on their staff.

The fact that fake scientists with a publication history were invited to review papers more often than were those without explains why paper mills would bother to publish papers under fake names in the first place, says Tim Kersjes, head of research integrity at Springer Nature in Dordrecht, the Netherlands.

It took Springer Nature two years to investigate this ring of fake scientists, eventually finding that they were probably the work of a China-based paper mill and retracting all of the affected papers by early 2021.

“Science has always been predicated on trust, and, at the time, awareness of identity fraud in peer review was limited. Such manipulation was rare, and editors were less alert to the risks,” Kersjes says. “We now have much more rigorous checks and editor training and awareness.” Kersjes presented his team’s investigation last month at the 10th International Congress on Peer Review and Scientific Publication in Chicago, Illinois.

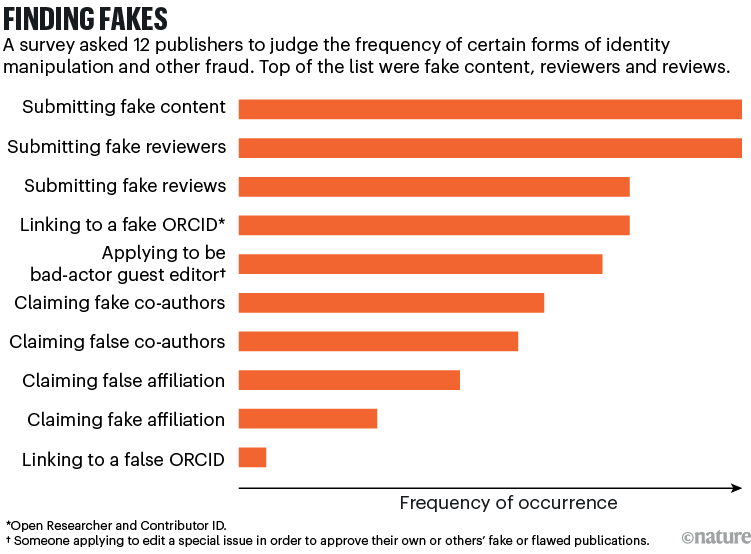

Fictitious personas are just one example of identity fraud. Individuals and paper mills can also impersonate real scientists, posing as authors, reviewers or guest editors to slip poor-quality or fabricated work into journals (see ‘Finding fakes’). In work published earlier this year1, software engineer Diomidis Spinellis at the Athens University of Economics and Business uncovered 48 articles in one journal that he suspected were generated by artificial intelligence (AI). One of them listed him as an author without his knowledge. Others named researchers at prestigious universities as co-authors, but used wrong or non-institutional e-mail addresses, and some of those researchers had died years before the publications.

Source: Ref. 4

Even working institutional e-mail addresses are not a foolproof test for identity fraud. A preprint2 posted in August identified 94 fake profiles on OpenReview.net — a platform used to manage peer-review workflows. All but two had e-mails that were tied to well-known universities; the remaining e-mails came from institutions that had already closed.

The analysis — done by a team including researchers from OpenReview — found that imposters created e-mail aliases of genuine institutional e-mails. These aliases forwarded incoming messages into e-mail accounts that the imposters controlled.

Checking up

It is unclear whether the number of cases of identity fakes in the scholarly publishing is growing. Elena Vicario, head of research integrity at Frontiers in Lausanne, Switzerland, says the situation is rare in Frontiers journals and typically involves impersonation of real individuals.

Richardson says that other forms of malpractice are probably of more concern. “My gut instinct is that people engaging in unethical or unscrupulous behaviour under their own name is a far bigger issue than people using somebody else’s name to engage in unscrupulous behaviour,” he says.

Nonetheless, cases of fictitious and hijacked personas continue to surface, and some people worry that AI might worsen the problem. So pressure is mounting on publishers to tighten their checks.

One platform publishers are increasingly using is the Open Researcher and Contributor ID (ORCID), which was launched in 2012 as a free identification service that individuals can use to record their academic papers and other research activities. Some 10 million researchers use ORCID at least once a year, and major publishers require submitting authors to include their unique ORCID 16-digit identifier. Registered researchers carry their identifier for the entirety of their career, even if they change their job or institute.

ORCID does not, however, provide proof of identity. Anyone can sign up on the platform and there is currently no systematic mechanism to prevent or remove duplicate accounts.

But the platform does ask its almost 1,500 member organizations, which include publishers and funders, to contribute to its records by confirming affiliations, works, funding or peer review. These verified entries — referred to as trust markers — show up as green ticks on researchers’ profiles.

Europe’s largest paper mill? 1,500 research articles linked to Ukrainian network

“It is a community trust network,” says Tom Demeranville, the UK-based product director at ORCID, which is a non-profit organization in Bethesda, Maryland. “If everyone does this, we have a very helpful system for everyone.” About 5.7 million ORCID accounts contain at least one trust marker.

But some publishers request ORCID identifiers for only the lead authors on a submission3, which limits how effective the system can be.

ORCID might therefore work better when combined with other strategies. That was one conclusion of an expert task force on identity checks set up in late 2023 by the International Association of Scientific, Technical & Medical Publishers (STM), a trade organization in The Hague, the Netherlands.

The goal was “looking at other tactics to bolster research integrity” beyond screening the manuscript, says Hylke Koers, chief information officer at STM Solutions, STM’s operations arm based in Utrecht, the Netherlands.

The task force has published two reports on its findings4,5. The latest, posted in March, recommends a framework that combines indicators of risk and trust that publishers could apply to determine how much confidence to place on identity verifications5. Any approach must accommodate multiple solutions because otherwise it risks wrongly excluding individuals, says Koers, who helped to compile both reports. “We don’t believe there is a single silver bullet here,” he says.

Alongside ORCID trust markers, the report suggests vetting institutional e-mail addresses and confirming affiliations through institutional sign-in systems. The framework also offers fall-back options such as making phone or video calls to the researcher or university, or requesting identity certificates or passports.