Donald Trump and the Iran Crisis

“History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.” Whether or not Mark Twain ever really said that line, it fits and resonates loudly as President Trump shuttles between the Oval Office and the Situation Room, weighing if he should dispatch bombers on yet another American sortie to the Middle East.

First, the necessary caveats. Since seizing power, in 1979, Iran’s theocracy has menaced its more than ninety million citizens and the wider region. The ayatollahs have deprived the country of a prosperous civil society, channelling resources instead into militarism and messianic fantasy. The regime relies on repression—crackdowns, imprisonment, torture, executions—to maintain control of a stifled and restive population. Many among the country’s educated élite have emigrated. The ranks of the leadership are staffed, in large measure, with satraps and mediocrities. Iran’s pursuit of nuclear weapons in tandem with its nuclear-energy project has proved a pointless catastrophe—most of all for the Iranians themselves. As Karim Sadjadpour, an Iran expert at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, notes, the nuclear program has been a practical and a strategic “albatross”; it supplies only about one per cent of Iran’s energy needs but has cost up to five hundred billion dollars in construction, research, and the penalties of international sanctions.

Meanwhile, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei—the Supreme Leader since 1989 and now eighty-six years old—pursues his regime’s martial goals and ominous fantasies. In 2015, he vowed that Israel, which shares no border with Iran, would disappear by 2040. The regime has projected force through the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and has bankrolled proxy militias throughout the region: Hezbollah, in Lebanon; Hamas, in Gaza; the Houthis, in Yemen; and, in Iraq, the Islamic Resistance. Armed and advised by Tehran, these groups have all carried out lethal operations.

For decades, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has called the Iranian nuclear enterprise intolerable, both for Israel and for the world. In many ways, Netanyahu is a flagrantly duplicitous politician; there is little he won’t say or do to maintain his coalition and his power. But he is right in this: a nuclear-armed Iran would threaten Israel (which has had nuclear weapons for decades) and could provoke Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Egypt, and others to pursue such a weapon, too.

No American President has ever disputed the peril of a nuclear-armed Iran. Yet when the Obama Administration managed to forge a nuclear deal, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, Netanyahu denounced it as weak. Donald Trump concurred, if only to show disdain for Obama. In 2018, Trump walked away from the J.C.P.O.A.—a heedless move, since he had no alternative to offer. That has left a dangerous vacuum.

In the wake of the Hamas attacks of October 7th, the political psychology of Israel has changed immeasurably. The original promise of the Israeli state was to end, once and for all, the dependency and the powerlessness of an exilic people who had suffered antisemitic persecution for centuries—a dark history that reached its nadir in the Nazi death camps. For Israelis, the Hamas attack represented not only the bloodiest day in the country since its founding but also the nightmarish return of vulnerability. On October 7th, the state failed: intelligence reports on Hamas’s intentions were ignored or dismissed; the Army was largely deployed elsewhere. That day, Hamas sought to inflict maximal suffering on Israel; it also aimed to rouse all of Iran’s proxies, perhaps even Iran itself, to join the fight.

But what Yahya Sinwar, the Hamas leader in Gaza, hoped would be the final battle for liberation ended in defeat and misery. Israel, in its fury, decimated Hamas and wiped out its leadership—including Sinwar—and also killed tens of thousands of Palestinian civilians. Entire cities and towns—Rafah, Khan Younis, Jabalia—have been flattened, or nearly so. Moshe Ya’alon, once Netanyahu’s defense minister, called the operation “ethnic cleansing” and accused the government of abandoning the hostages taken by Hamas and “losing touch with Jewish morality.”

While the Israeli government absorbed international condemnation for its excesses and crimes in Gaza, its forces fought with relative precision in Lebanon, killing nearly all of Hezbollah’s leadership and thousands of its fighters. Not long afterward, the Assad regime in Syria—having slaughtered hundreds of thousands of its own people with Iranian support—collapsed.

This was the moment of weakness in Tehran that Netanyahu had been waiting for. Israeli intelligence appears to have penetrated the Iranian regime and its security bureaucracies even more thoroughly than it had Hezbollah. In the past two weeks, Israel has eliminated the uppermost ranks of Iran’s military and intelligence leadership and of its nuclear scientists. But it did not take long for Netanyahu’s rhetoric and tactics to shift—from a focus on the attacks against military and nuclear sites to broader, more perilous ambitions. Israel has attacked Iran’s main television center and the Greater Tehran Police Command; these are symbols of the government, not military targets. Netanyahu, asked by ABC News if he was targeting Khamenei himself, replied, dryly, “We are doing what we need to do.”

But history insists on its own lessons. The early triumphal days of “overwhelming force” and toppled monuments are nearly always followed by the unforeseen: sectarian conflict, insurgency, terrorism, chaos. We have been here before often enough to have realized that the fantasy of regime change is rarely, if ever, realized. No people, it turns out, welcome their “liberation” by foreign invaders. And, as a recent report in the Wall Street Journal notes, should Khamenei be toppled or killed, it is the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, which maintains enormous economic as well as military influence, that could be in position to name a new ruler and “assume unprecedented power.”

So what will Trump do? Israel has already struck and badly damaged the uranium-enrichment facility at Natanz, the Isfahan Nuclear Technology Center, the heavy-water reactor at Arak, and other sites. Yet most experts agree that the crucial target is the enrichment center at Fordo, which is embedded deep inside a mountain. It is widely assumed that the sole weapons capable of destroying Fordo are the Massive Ordnance Penetrators—American-made “bunker-buster” bombs weighing thirty thousand pounds each. Only American B-2 bombers are capable of carrying them. Netanyahu has hinted that Israel might have its own ways of degrading Fordo, perhaps with some sort of ground operation, but he clearly prefers that Trump order U.S. pilots to do the job.

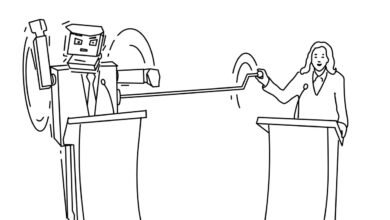

There is not an American President—Bill Clinton, George H. W. or George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Joe Biden, or Donald Trump—who has dealt with Netanyahu and not, sooner or later, come away with a lingering sense of resentment. Netanyahu exudes preternatural confidence in his powers of manipulation. In 2001, during a meeting with Israeli victims of terrorism, he assured them that he could always bring the United States around. “I know what America is,” he told them. “America is a thing you can move very easily, move it in the right direction.”

It’s not easy to trust Donald Trump to make an optimal decision. For one thing, he is suspicious of nearly every source of information save his gut. He revels in uncertainty. (“Nobody knows what I’m going to do.”) He has hollowed out the staff and the expertise of the National Security Council. He appears to disdain his director of National Intelligence, Tulsi Gabbard, and her conclusion that Iran’s pursuit of a nuclear bomb is not nearly as advanced as Netanyahu claims. He fired his national-security adviser Mike Waltz but, rather than replace him, merely handed the additional duties to the Secretary of State, Marco Rubio. Trump’s Metternich is Steve Witkoff, a modestly accomplished New York real-estate developer; his Defense Secretary, Pete Hegseth, formerly a weekend Fox News host, has, at last, struck the President as an empty suit with a pompadour. (According to the Washington Post, Hegseth has been sidelined.) In the meantime, Trump must pay attention to the insights provided by rival camps in his MAGA universe: the isolationism of Steve Bannon and Tucker Carlson versus the interventionism of Mark Levin and Laura Loomer.

Trump has set a deadline of two weeks for rumination and negotiation. History offers cold comfort and little clarity. Philip Gordon, a senior foreign-policy adviser to President Obama and Vice-President Harris, once reflected on the dismal outcomes of recent U.S. military interventions in the Middle East. Writing in Politico, in 2015, he noted:

Now, a decade later, yet another Middle Eastern crisis is here, and it rests in the hands of the American President and the Supreme Leader. In nearly all things, military matters included, Trump is hardly a model of discernment. He recently dispatched marines to cope with “insurrectionists” protesting his immigration policies in downtown Los Angeles, even as he cast the actual insurrection at the Capitol, four years ago, as “a day of love.” Meanwhile, Khamenei must now consider backing down as never before. His predecessor, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, once likened signing a truce with Iraq after a decade of war to “drinking poison.”

The self-intoxication that can accompany the early days of battle––the euphoria of “shock and awe,” the dreams of frictionless regime change—once again stands in the way of rational negotiation. To avoid a wider conflagration in Iran, Israel, and beyond, the American President will have to temper his worst impulses for a “quick win” and negotiate. The Ayatollah, for his part, like his predecessor, will have to lift the chalice to his lips and take a sip. ♦