Bob Weir’s Feral Radiance | The New Yorker

Although Weir was a serious person it was easy to make him laugh. He made you feel when you were with him that he had no other place to be, that things had worked out to bring the two of you together, and that he meant to enjoy this gift from life. He could also be unreachable when a dark mood was upon him, but it always seemed a sort of neurological unreachability, a matter of his wiring, rather than an emotional one. Sometimes we would talk about my son, who is autistic, and Weir would say, “I’m autistic, too.” He might have been, mildly; it’s hard to know. His friend John Barlow, with whom Weir wrote a number of songs, once told me, “Bob marches to the beat of a different drummer, and it might not be a drummer at all.”

He had insomnia, and he struggled plenty with drinking and with sleeping pills, and did stints in rehab. Sometimes when I was with him he would be abstaining from alcohol, and other times he would drink. When he drank, he was mostly solemn and silent.

The first time I met Weir, I didn’t think he was very smart. I’d expected to meet someone who had a life of the mind and found the same pleasure in reading that I do. Weir eventually explained that he was severely dyslexic, to the point that even trees on a hillside sometimes switched places in his mind’s eye. Over time, I realized that he had an original and penetrating mind, one developed from what he heard, what he saw, what came to him in his imagination.

He loved football. I can remember the pleasure of hearing him say, about playing the sport in high school, “I was flipped out about football.” He was a scrawny kid, but he was fast and totally fearless and would do anything the coach told him to. I realized that sports had been an essential model for him as a musician. It had given him a way of finding a place in the Grateful Dead—enacting a role as a member of a crew. For the rest of us, the Grateful Dead was a band, but I think for Weir it was a team. He was a permanent teen-ager, but of a rarified kind—not so much stuck fast in a period as still capable of visiting the sanctified territory of wonder and deep engagement. He had maintained a connection to the place where big dreams come from.

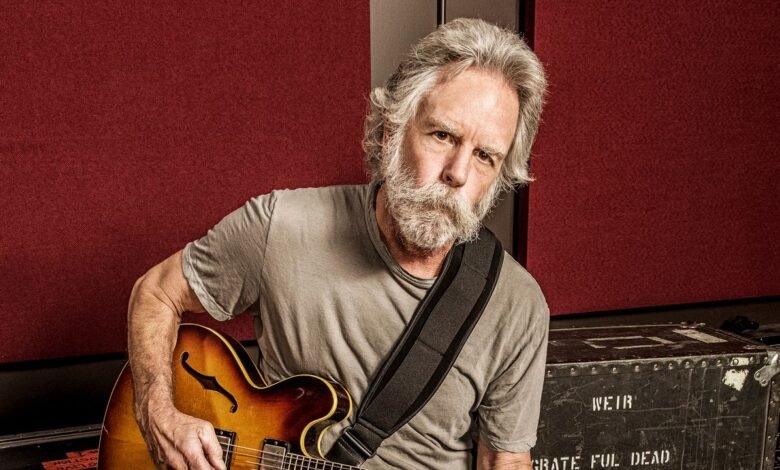

There was a raised-by-wolves quality about him, a kind of loopy, feral radiance. He had been brought up by prosperous adoptive parents, but he’d found his biological father later in life. One night in Stinson Beach, seven or eight years ago, after we had gone to dinner and come back to the house, I asked about Weir’s childhood, and he answered at some length. “As a matter of record, I was born Steven Lee Sternia in San Francisco, in 1947,” he said. “Sternia—‘of the stars’—was an assumed name, an alias basically, and didn’t belong either to my mother or father, who weren’t married to each other, or married at all. They had been living in Tucson, where they were students at the University of Arizona—my mother was studying drama. My father had been in the Air Force, and he was going to school on the G.I. Bill. I heard he’d been the youngest bomber pilot in the Air Corps, having flown, I think, a Martin B-26 Marauder in the war. The B-26 was mainly for troop support, and it wasn’t all that maneuverable. It was slow and heavily armored, and it had stubby wings, and because it flew low, it took a lot of ground fire. It was known as the Widow-maker.

“The deception about my name was because my being born, my existing at all, was meant to have been kept a tidy secret from my mother’s family. She already had a daughter, born a few years earlier, somewhere between Ohio and Arizona. She believed that if her family found out about me, they would think that she was reckless and unfit as a mother and take the daughter from her, although I’m not even sure she exactly still had the daughter. Or maybe they already thought she was reckless and unfit, and she didn’t want to give them the satisfaction of being proved right. According to my birth certificate, her first name was Phyllis. When I tried to find her years later, with a private detective, he told me that she had covered her tracks. Anyway, I was adopted at birth by Eleanor Claire Cramer and Frederick Utter Weir.