Anatomy (not Autopsy) of the Phillips Curve

The relationship between inflation and real economic activity has long been central to debates in macroeconomics and monetary policy. At the core of this debate is the Phillips curve (PC), which measures how strongly inflation reacts to movements in economic conditions. The steepness of this curve matters enormously for monetary policy: if the PC is steeper, inflation rises faster during booms and falls faster in recessions, which entails central banks having to act more forcefully if they want to stabilize inflation around their target. Prior analysis found astonishingly small estimates of the slope of the PC, which suggests that the curve is “flat” (or even dead). In this post, I present evidence from coauthored research showing that, contrary to the conventional view, the Phillips curve is alive and steep, and it captures inflation volatility remarkably well once real marginal cost is used instead of standard real economic activity measures.

The Conventional Formulation of the Phillips Curve

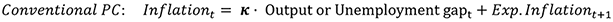

The Phillips curve links inflation to expectations of future inflation and a measure of economic slack. In the conventional formulation of the PC, economic slack is typically proxied by the output or unemployment gaps—the deviation of output or employment from its natural level:

In this view, inflation rises when the economy overheats and falls during slowdowns. The slope of the Phillips curve, K in the equation above, captures how sensitive inflation is to these fluctuations. A large body of research finds that the PC is quite flat—the slope is very small—implying that inflation hardly moves in response to shifts in output or employment gaps. These findings have long puzzled economists and fueled debate about how active monetary policy should be to steer inflation.

The Primitive (Cost-Based) Formulation of the Phillips Curve

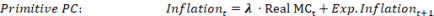

There is another way to think about inflation dynamics and its drivers. At its foundation, the Phillips curve emerges from the aggregation of firms’ pricing decisions in response to changes in production costs. In the primitive formulation of the PC, the variable influencing inflation is real marginal cost in percentage deviation from trend, rather than the output or unemployment gap:

In this view, inflation rises when economic forces increase firms’ production costs. The slope of the curve reflects how strongly (and quickly) these costs are passed through into output prices.

The Slope of the Cost-Based Phillips Curve

The cost-based formulation makes it easier to understand the key forces that determine the slope of the PC. In theory, if markets were perfectly competitive and frictionless, prices would move one-for-one with costs: any increase in wages or input prices would be instantly reflected in consumer prices. That is, the slope would be one.

Reality is very different. Firms typically adjust prices infrequently, since doing so involves both direct costs (such as relabeling or updating systems) and indirect costs (such as confusing customers or losing goodwill). In addition, firms often set prices strategically, choosing to delay changes until they are sure cost pressures will last, or timing revisions to match competitors. Thus, frictions that lead to infrequent price changes and strategic considerations in price setting weaken the transmission of cost shocks into prices. The more firms deviate from the ideal of flexible, competitive markets, the flatter the Phillips curve becomes.

Estimating the Slope of the Cost-Based Phillips Curve Using Microdata

How steep is the cost-based PC in the data? Answering this question is notoriously difficult, particularly when the estimation is solely based on aggregate data in which many shocks influence inflation and real activity at the same time. To address this problem, we turn to firm-level evidence. In a recent paper coauthored with Mark Gertler (New York University), Luca Gagliardone (Yale University), and Joris Tielens (National Bank of Belgium), we use detailed microdata on prices and costs to study how individual firms adjust their prices in response to changes in production costs. This approach allows us to quantify how nominal rigidities (infrequent price changes) and real rigidities (strategic interactions among firms) dampen the response of prices to cost shocks. With these estimates we recover the slope of the primitive form of the Phillips curve.

Our analysis suggests a strong link between inflation and real economic conditions, as captured by producers’ costs. On average, firms keep prices fixed for three to four quarters, confirming a substantial degree of nominal rigidity. We also find strong evidence of strategic complementarities: firms adjust less aggressively because they prefer to move in step with competitors, which cuts the pass-through of cost shocks roughly in half. Taking these frictions into account, we estimate the slope of the cost-based Phillips curve to be three to ten times larger than the estimates for the output- or unemployment-based PC formulation. This implies that the Phillips curve is steep, not flat, even in normal times.

Accounting for Aggregate Inflation Dynamics

Cost pass-through plays a dominant role in shaping aggregate inflation. To illustrate this, we build a cost index by combining firm-level changes in labor and input costs and then feed it into the cost-based Phillips curve. Using the Belgian manufacturing sector as a case study, we construct a model-generated inflation series by feeding data on costs into the Phillips curve. The results, shown in the chart below, show that the predicted inflation aligns very closely with actual producer price inflation (PPI) in Belgium. The two series are highly correlated, with a correlation coefficient above 80 percent; quantitatively, movements in production costs alone account for about 70 percent of observed inflation fluctuations, highlighting the central role of costs in driving inflation dynamics.

Through the Lens of the Cost-Based Phillips Curve, Fluctuations in Production Costs Account Well for Inflation Volatility

Notes: The blue line represents the time series of manufacturing PPI in Belgium. The red line is the model-implied manufacturing PPI obtained feeding an aggregate cost index to a cost-based PC.

Reconciling the Steep Cost-Based Phillips Curve with the Flat Output-Based Phillips Curve

These results raise a natural question: Why does the cost-based Phillips curve slope steeply while the output-based one appears flat? And are these findings at odds with previous research?

Our research shows that the “flatness” of the conventional Phillips curve reflects a weak link between output gaps and marginal costs. In other words, while production costs feed directly into firms’ pricing decisions, movements in output (or unemployment) bear only a loose relationship to inflation.

From a conceptual standpoint, the conventional PC holds only if marginal cost and the output gap move proportionally—an assumption that requires, among other things, perfectly flexible wages. When these conditions fail, the output gap may be a poor proxy for real marginal cost, biasing estimates of PC downward. Moreover, even if proportionality roughly holds, the output-based slope equals the cost-based slope scaled by the elasticity of marginal cost with respect to output. If this elasticity is low, the slope of output-based PC will be low as well, even if the slope of the cost-based PC is sizable.

These results are confirmed in the data. Focusing on the pre-pandemic period (1999–2019), we estimate a very low elasticity of marginal cost with respect to output. This finding helps explain why the cost-based PC is steep while the conventional PC looks flat.

Lessons for the Post-Pandemic Inflation Surge

Our findings show a strong pass-through from marginal costs to prices, which explains why the cost-based Phillips curve matches inflation dynamics so well. The weak link between output and marginal cost, on the other hand, helps explain why the conventional output-gap version of the PC looks “flat.” In normal times, two factors drive this low elasticity: firms’ cost schedules tend to display nearly constant short-run returns to scale, so marginal costs barely move with output; and wage rigidity further dampens any feedback from demand to costs.

The pandemic and its aftermath revealed how quickly these relationships can change under stress. Severe shocks—whether from labor market tightness or supply chain bottlenecks—pushed firms against capacity limits, sending marginal costs sharply higher and fueling inflation. At the same time, the slope of the Phillips curve itself can shift. Pre-pandemic data showed stable adjustment frequencies and an approximate linear relationship between inflation and (percentage) changes in real marginal costs. More recently, however, firms have been adjusting prices much more often, raising the elasticity of inflation with respect to costs and generating nonlinear inflation dynamics. I will talk about nonlinear inflation dynamics—what it means, how it works, and what it implies—in a companion post on Liberty Street Economics.

Simone Lenzu is a financial research economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Simone Lenzu, “Anatomy (not Autopsy) of the Phillips Curve,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, February 4, 2026, https://doi.org/10.59576/lse.20260204

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).