Quantum computers will finally be useful: what’s behind the revolution

Just a few years ago, many researchers in quantum computing thought it would take several decades to develop machines that could solve complex tasks, such as predicting how chemicals react or cracking encrypted text. But now, there is growing hope that such machines could arrive in the next ten years.

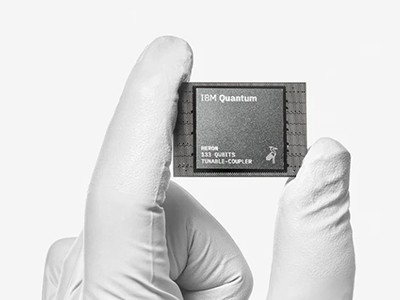

IBM releases first-ever 1,000-qubit quantum chip

A ‘vibe shift’ is how Nathalie de Leon, an experimental quantum physicist at Princeton University in New Jersey, describes the change. “People are now starting to come around.”

The pace of progress in the field has picked up dramatically, especially in the past two years or so, along several fronts. Teams in academic laboratories, as well as companies ranging from small start-ups to large technology corporations, have drastically reduced the size of errors that notoriously fickle quantum devices tend to produce, by improving both the manufacturing of quantum devices and the techniques used to control them. Meanwhile, theorists better understand how to use quantum devices more efficiently.

“At this point, I am much more certain that quantum computation will be realized, and that the timeline is much shorter than people thought,” says Dorit Aharonov, a computer scientist at Hebrew University in Jerusalem. “We’ve entered a new era.”

Error prone

The latest developments are exciting to physicists because they address some of the main bottlenecks preventing development of viable quantum computers. These devices work by encoding information in qubits, which are units of information that can take on not just the values 0 or 1, like the bits in a classical computer, but also a continuum of possibilities in between. The prototypical example is the quantum spin of an electron, which is the quantum analogue of a magnetic needle and can be oriented in any direction in space.

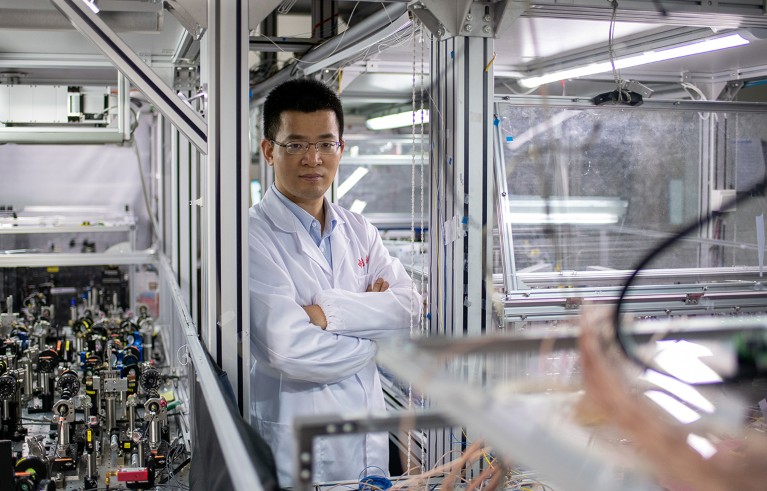

Chao-Yang Lu is among those who expect a fault-tolerant quantum computer by 2035.Credit: Dave Tacon for Nature

The heart of a typical quantum computation consists of a series of gates, which are operations that manipulate the state of qubits. Gates can be performed on a single qubit, for example rotating a spin by a certain angle, or on more than one qubit. Crucially, a gate can put multiple qubits in collective entangled, or strongly correlated, states — exponentially boosting the amount of information that they can handle. Every computation then concludes with a measurement, which extracts information from the qubits, destroys the intricate quantum state produced by the gates and returns an answer in the form of a string of ordinary digital bits.

For decades, researchers questioned the viability of this computational paradigm owing to two main reasons. One is that, in practice, quantum states tend to naturally and randomly drift, and after a certain amount of time, the information they store is inevitably lost. The other is that gates and measurements can themselves introduce errors. Even operations as simple as using electromagnetic pulses to rotate a spin never work out exactly as intended.

But over the past year or so, four teams have shown that these problems are ultimately solvable, Aharonov and others say. These groups hail from the Google Quantum AI lab in Santa Barbara, California1; Quantinuum, a company in Broomfield, Colorado2; and Harvard University and the start-up company QuEra3, both in the Boston, Massachusetts, area. Just last December, a fourth team, at the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) in Hefei, also joined this exclusive club4.

The four groups implemented — and improved — a technique called quantum error correction, in which a single unit of quantum information, or ‘logical’ qubit, is spread across several ‘physical’ qubits.

This billion-dollar firm plans to build giant quantum computers from light. Can it succeed?

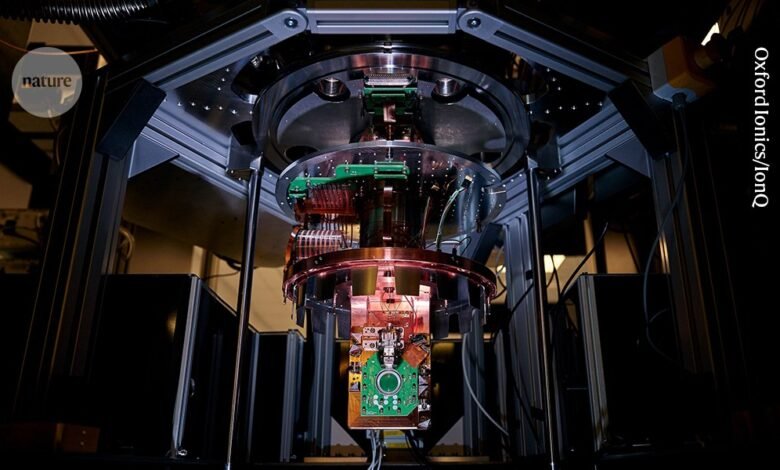

In the work from the Google and USTC teams, quantum information is encoded in the collective state of electrons circulating inside a loop of superconducting material, kept at a whisker above absolute zero to prevent the information from degrading. Quantinuum uses the magnetic alignment of electrons in individual ions in an electromagnetic trap. And QuEra’s qubits are represented by the alignment of individual neutral atoms confined by beams of light that act as ‘optical tweezers’. By measuring specific physical qubits halfway through a computation, the machine can then detect whether the information in a logical qubit has been degraded and then apply a correction.

Like any operation on qubits, the correction itself introduces errors. In the 1990s, Aharonov and others proved mathematically that, if applied repeatedly, the process can reduce errors by as much as is desired. But the result came with a catch: each of the steps in error correction has to reduce the error below a certain threshold.

The four teams have now demonstrated that their computations can satisfy that requirement. To many physicists, this watershed moment demonstrated that large-scale, ‘fault tolerant’ quantum computing could be viable.

Nines aplenty

Even when it works, quantum error correction is not a panacea. For a long time, scientists estimated that using it to run a fully fault-tolerant quantum algorithm would require an overhead of 1,000:1, or at least 1,000 physical qubits for each logical qubit. The largest quantum computers built so far have just a few thousand qubits — but early estimates suggested that billions might be needed to do things such as factoring into prime numbers.

Andrew Houck (pictured), Nathalie de Leon and their colleagues at Princeton University developed a technology that could make quantum computing more accurate.Credit: Matt Raspanti/Princeton University

This task has long been a benchmark because quantum computers that can factor large numbers into primes would be powerful enough to solve previously intractable problems, such as predicting the properties of new ‘wonder materials’ or making stock trading super efficient.

One thing that has helped in achieving these goals is implementing algorithms in a clever way, using fewer qubits and gates. This has reduced estimates of the number of physical qubits it would take to factor large numbers — which would break a common Internet encryption system — by roughly an order of magnitude every five years. Last year, Google researcher Craig Gidney showed that he could cut the number of qubits down from 20 million to one million5, in part by arranging abstract gate diagrams into complex 3D patterns. (“I do use a lot of geometric intuition,” he says.) Gidney says his implementation is probably close to the best possible performance of a standard quantum-error-correction technique. Better ones, however, could bring the overhead down further, he adds.

Quantum computing ‘KPIs’ could distinguish true breakthroughs from spurious claims

“The whole name of the game right now is how you can make error correction more efficient,” says de Leon — and there are several possible approaches. Theoreticians can help by developing error-correction techniques that encode the information of a logical qubit more efficiently, thereby requiring fewer physical qubits. And improving the ‘fidelity’, or accuracy, of gate operations and the quality of physical qubits means that fewer error-correction steps will be needed, thereby lowering the necessary number of physical qubits. Jens Eisert, a physicist at the Free University of Berlin, says he “would be surprised” if physical-qubit overheads did not come down further in the next few years.

“I think, mathematically, the theory of quantum error correction is getting richer and more interesting. There’s been a huge explosion of papers,” says Barbara Terhal, a theoretical physicist at QuTech, a quantum-technology research institute, supported by the Dutch government, at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. She warns, however, that complex error-correcting codes could have drawbacks because they make it more complicated to perform gates.

One such technique, perfected by IBM, promises to encode logical qubits using one-tenth the number of physical qubits as industry-standard approaches, or an overhead of roughly 100:1. QuEra is experimenting with methods that lean on a major strength of its ‘neutral atom’ qubits: the flexibility to be moved around to be entangled with one another at will. Their error-correction approach, too, could in principle lower the overhead to 100:1, says Quera founder Mikhail Lukin, a Harvard physicist. To get there, Lukin reckons that the fidelity of his two-qubit gates, currently hovering at 99.5%, will have to grow to about 99.9%, which he says is feasible. “We are well on the path to ‘three nines’,” he says, using the industry’s term.

De Leon, meanwhile, has focused on studying the weaknesses of qubits using advanced techniques in metrology, the science of precise measurements. Historically, a major drawback of superconducting qubits has been their short lifetimes, which cause stored information to degrade even as the algorithm manipulates physically distant qubits on the same chip. “The qubits die a little bit while they’re waiting for you to do the gate,” says de Leon. She and her collaborators conducted ultra-precise measurements of superconducting qubits to isolate the sources of electromagnetic noise that limit their lifetimes. They then tried switching from superconducting loops made of aluminium to ones made of tantalum, and the supporting material from sapphire to insulating silicon. Together, the changes boosted the lifetime from 0.1 milliseconds to 1.68 milliseconds, the authors described in a Nature paper in November6. She says there is room for further improvement. “There are obvious things to try, where I believe we can get to 10 or 15 milliseconds,” de Leon says, although she also warns that often, after removing one source of noise, another unexpected one creeps in.