creative solutions for time-starved researchers

Illustrations: Richard L. Tillotson

Art and science have a long and intertwined history. During his five-year research trip on HMS Beagle, Charles Darwin drew his own finches; and Marianne North, his contemporary, was both a prolific painter and a botanist who set up a dedicated gallery at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, in London. Their artistic endeavours, and those of other researchers, demonstrate that the connection between science and art is more profound than simply representing the world around us — both fields are inspired by the search for truth.

Educational systems are often set up to make us think that if you do one, you don’t need the other. However, it is becoming increasingly clear to the authors that the same tools of creativity, critical thinking, problem solving and challenging the status quo are required for both.

We met around 15 years ago at a friend’s wedding, eating hog roast in the shadow of Scafell Pike, a mountain in the Lake District, UK, while keeping an eye on our respective toddlers. We are united by a passion for cricket, BBC Radio’s Test Match Special and the absurd. While talking about our respective careers (R.T. works in illustration, J.T. in immunology), we identified a number of shared practices that help us in the quest for ideas. To widen the net, we then interviewed others in creative fields for further advice to help us to cross the boundary between art and science.

We’ve distilled the advice that we received from people working in music, literature, show business and comedy into this piece, along with accompanying illustrations, to help scientists to reach their creative peak.

Setting neuron your way

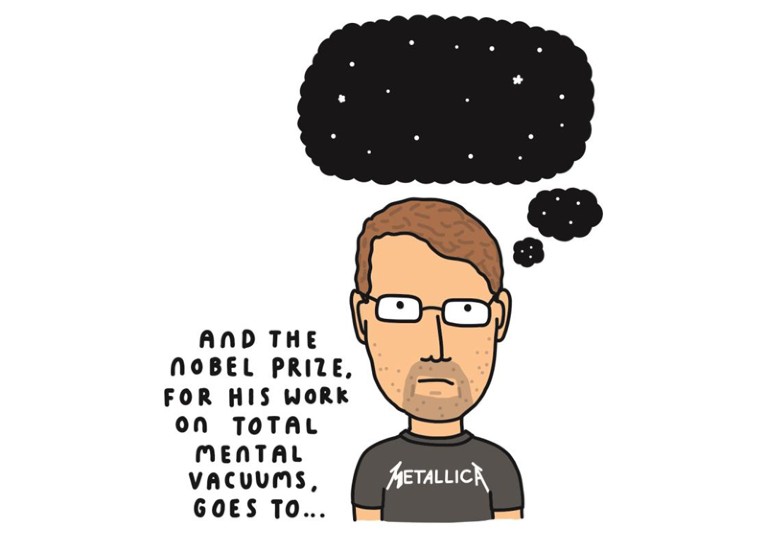

The first thing we agreed on is mindset. For creativity to happen, we both find that our brains need to be in a specific state, sometimes referred to as the default mode network1. This is the daydreaming, dissociative state in which free-flowing ideas occur and unexpected connections can be made.

Creative breakthroughs, eureka moments or ideas for cheese-themed greetings cards (if you are R.T.) come when previously unconnected groups of brain cells connect in new and interesting ways.

And there is nothing you can really do to force these connections to happen, which can be frustrating when you are up against a deadline. British punk/folk singer-songwriter Frank Turner told us: “My creative process is like fishing: you find your spot by the river and cast your bait, and then wait to see what comes. Good days and bad.”

Applying Turner’s songwriting thoughts to drafting an academic paper, you might think that trying to squeeze 30 minutes of writing in between incubation steps in the laboratory is time-efficient, but we find that this sort of approach never works. The cognitive switch between the attention to detail required to do lab work, so that you don’t lose track of whether you added the right reagent to the last of 96 identical wells, and the free-flowing dissociative state needed for creation is nigh on impossible. To be time-efficient, J.T. has learnt to fill gaps in lab work with the boring admin work that takes time but doesn’t need creativity.

Time and place

One thing that can help the mindset is place; certain spaces lend themselves better to creativity. But it is not a ‘one size fits all’ solution. J.T. wrote a lot of the first draft of his new book Live Forever? on the London Underground, probably because there is no distraction from the Internet.

Time is another key variable. There are periods when people are more productive. Discussing peak periods of productivity, we identified times of the day at which ideas come more easily. Underpinning these are circadian rhythms: there really are larks (people who are at their best in the morning) and owls (who peak later in the day). Chronotype, or diurnal preference, is driven by mutations in the clock genes2.

Without the guidance of the Sun and other cues, our body clocks reset to a genetically determined day length that can vary between 24.1 hours in larks and 24.3 hours in owls. One paid-for genetic-screening test revealed that the ‘natural’ time for J.T. to wake up at is 07:42. These preferences are reflected in a morningness–eveningness questionnaire3: J.T. scored as an intermediate and R.T. was ‘moderate morning’.

Knowing your preferences and then building routines around them helps. Helen Fields, author of the DI Callanach thriller series, told us: “I make sure I have hot tea in front of me and play the same music playlist over and over again. I think it’s taught my brain — here we are, get into position, you know what’s about to happen — and that’s when the focus comes. It feels the same as an athlete going through the same steps before starting a race.”

No matter how perfect the mindset, how well prepared the space, how much you have shut out distractions, there are days when it just doesn’t work. You sit there and all you end up with are crumpled sheets of paper, empty canvases or blank text files. But what is hard to tell is whether these days are truly wasted. When the ideas stop, we both find that it helps to step away from the desk. Go for a walk, even if it’s to the smallest room in the house. Most of the best ideas come when you step away.

Ben Willbond, actor and screenwriter of the BBC children’s comedy TV series Horrible Histories, told us: “Running helps me unpick creative problems; it provides a separate time to think.” By separating himself from the work, he can clear his head and unlock the problem.

We do the same: R.T. paces the Pennine Hills near his home in northern England, pondering puns about parmesan; J.T. runs through London’s Hyde Park, chasing squirrels and fleeting hypotheses.

Sketching things out

We both regularly use a large notebook that acts as a working space. In it, ideas can hang out with other ideas. R.T.’s sketchbooks are not full of pristine renderings of Michelangelo’s David; they’re messy melting pots of mind maps, crossword attempts, doodles and shopping lists. This random nature helps to trigger unusual connections.