Jeff VanderMeer on How Scientific Uncertainty Inspires His Weird Fiction

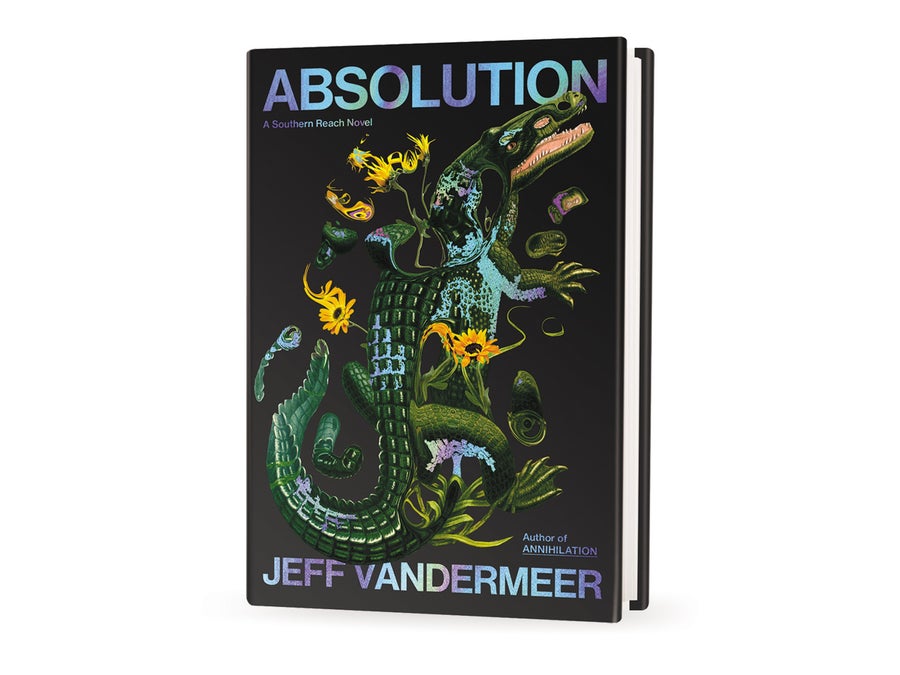

Few novelists are as adept at inspiring both horror and awe as Jeff VanderMeer. The author is perhaps best known for his award-winning Southern Reach series, of which the first three installments—Annihilation, Authority and Acceptance—were published in 2014. The books follow cadres of scientists on expeditions into Area X, a swath of pristine wilderness along Florida’s coast where nature has inexplicably shifted, changing not only itself but anyone or anything deemed a threat to its existence.

None of VanderMeer’s novels is easy to categorize, but many fall within the tradition of weird fiction, a genre that combines elements of fantasy and science fiction while trafficking in the unknowability of the universe. The genre is at its most skittering, most slithering and most uncanny in VanderMeer’s world, where wild landscapes and their inhabitants take on traits usually ascribed to humans: plants and the sky itself seem to watch; rabbits look as if they understand; insects are simply too aware.

This month VanderMeer continues this weird saga with the publication of the fourth Southern Reach novel: Absolution. Like its predecessors in the series, it’s rife with humor, horror and a visceral compassion for the natural world. Told in three parts, it exemplifies the author’s keen attention to detail and narrative structure, qualities in his writing that he says were informed by an interest in science. “I’m interested not only in science but in the narrative of science, how science corrects itself over time,” he says in a video call from his home in Tallahassee, Fla. Like weird fiction, he adds, “science can’t ever explain everything because we are continually learning new things.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Scientific American spoke with VanderMeer about his latest novel, as well as the reason he feels environmental education for young people is needed now more than ever.

[An edited transcript of the interview follows.]

It’s been 10 years since you published the first three books of the Southern Reach series. What inspired you to write a fourth?

I read part of a story I was working on at a convention called Readercon in the [summer] of 2023 and got a great reaction, and that sparked something. In the months that followed, I had a series of, I guess you would call them setbacks, to my writing because I got involved in local politics, which are kind of toxic here [in Florida]. Then, suddenly, I had the whole vision for the novel in my head. I started writing, and it was ridiculous. I wrote continuously up until the end of the year, every day, morning, noon and night. It was just pouring out of me to the point where I had to hire a research assistant, Andy Marlowe, to go down to the Forgotten Coast [region of Florida] and collect details for me. I knew if I stopped for research, I’d somehow interrupt something. Andy brought so much to this project. Even when their research didn’t necessarily make it into the book, there are scenes where the echoes of that research are still present.

I want to ask you about one of the most unsettling scenes I’ve read in a novel. It appears in a section called “The House Centipede Incident.” I live with a few house centipedes. For the most part, I let them be because I know they’re beneficial and eat the insects I really don’t want in my home. But they’re so very, very leggy. Without giving too much away, how did you come to write what you did about this creepy arthropod?

When I’m writing a novel, I don’t really seek inspiration out; it’s more like anything that comes to me gets devoured by the novel—if it’s a good fit. In the case of this scene, my best friend Laila texted me to say that she was horrified that she had stepped on Grandma, her favorite house centipede. She called it Grandma because it’d been in her home for at least a couple of years. It happened in the dark one night while walking to the bathroom, and her story stuck with me because I also had an unnerving experience with a house centipede. While teaching in South Carolina, a huge one rushed up to me. I swear to God this thing was almost six inches long; it must have been really old. I love them, but, you know, it was startling how it kind of reared up at me. While writing, I was thinking about both incidents and how people have a complicated relationship with centipedes, even people who like them. I wanted to dig into that a bit. Hearing about a friend’s real-life emotional reaction is so much more powerful to me than reading something for research.

They don’t even look like normal, slow-moving centipedes. They’re so fast.

I didn’t know that [the publisher of Absolution] was going to put pictures of house centipedes all over the book.

Let’s talk about the humans in your books. What inspired you to write about scientists?

It basically goes back to being surrounded by scientists my whole life. My dad’s an entomologist who studies fire ants and used to study rhinoceros beetles in Fiji when we lived there. One of my most vivid memories is of him trying to catch an invasive moth in Ithaca, [N.Y.], in the middle of winter. It started flying over this raging river, and he insisted on wading into the water. He caught it, but he was almost swept away by the current. My mom was a biological illustrator until computers took that over. And my stepmom is a lupus researcher. My sister helps create safe spaces for hedgehogs at the University of Edinburgh. With influences like these, it felt pretty natural to write about science, as well as human and nonhuman intelligence.

Would you say you inherited some of your family’s scientific curiosity?

Yes, definitely, from both parents. My mom’s biological illustrations and art provided a helpful way of looking at the world. And my dad, he was the kind of scientist who took a lot of pride in building up chains of evidence cautiously for years before writing. Some of his best papers took years of painstaking work, but ultimately, he made some amazing discoveries because of that careful approach. These were two vastly different ways of looking at the world, at details, but they kind of melded in me and in my fiction.

You write in a tradition called weird fiction. Uncertainty about how the universe works is a hallmark of the genre. Do you see any similarities between weird fiction and science?

At its best, weird fiction actually does something entirely different than what science does; it provides a venue outside of philosophy, science and religion to explore the unknown while incorporating elements of all three. At the same time, it features a lot of what you might call “scientific expeditions” into the unknown, where characters try, through rational methods, to know the unknowable. If they fail, it’s not necessarily a failure of science but a failure of the tools they were using or of the composition of the expedition. I find that quite interesting because failure exists in science, too, which sometimes appears in the form of bias. One of the more obvious examples is the pervasive idea that a fertilized human egg is a passive thing, that it’s the man that provides the active component of conception, when the relationship is much more complex than that. But because a lot of male scientists were the first to research this phenomenon, the more passive narrative persists.

Another outlandish example of bias can be found in a book called Penguins from the 1960s, which starts out as a beautiful, general book about penguins. But by chapter three, it is incredibly clear that the researcher who wrote the book hates this other [penguin] researcher. He’s writing about evolution but starts to make the book more about proving this other scientist wrong. In a way, this book of science also becomes a work of fiction because it’s shot through with the idiosyncrasies of the person writing it.

Do you seek out expert opinions from scientists when writing your novels?

I read a lot of nonfiction books, especially those in the environmental sphere, but I prefer to speak with experts directly. The way that scientists convey information to you is often very different than what you read in a book. One of my most notable collaborations was with the biologist Meghan Brown, who came up with the idea of a “hummingbird salamander,” the animal at the heart of my novel of the same name.

Speaking of unusual animals, you live in Florida, and in recent years you’ve emerged as a rather public advocate for biodiversity in the region. You even launched a nonprofit to protect Florida’s wild spaces. What do you see as the biggest threat to the state’s biodiversity?

The biggest threat literally comes down to who’s buying the land because land is being bought up quickly by developers, and there’s so little regulation around this. I spoke with an expert on North Florida plants, Lilly Byrd, who told me that there are areas in the state that serve as the last bastions of, like, a dozen rare plants. Without protection, those plants will go extinct, and something like four of those areas are slated to become gas stations. These plants that have existed for millions of years or whatever could go extinct because of gas stations. It’s really sad.

Our nonprofit, the Sunshine State Biodiversity Group, is small and can’t stop development on its own. So what we’re doing is getting grants that we can then contribute to larger efforts. We’re also working on environmental education for the public, which is sorely lacking in Florida, by funding groups such as local 4-H clubs and a clean-energy summer camp. One of the best ways to make a difference is by educating the next generation.