In Patriotic Melodies in the Civil War North, “Freedom” Wasn’t Necessarily a Cry for African-American Emancipation

Anyone who explores Civil War–era history should pay close attention to how people at the time understood and used key words. “Freedom” ranks among the most important of such words. Americans of the 21st century almost always address questions relating to freedom within a context of slavery and emancipation. This approach often yields insights regarding mid–19th century people, across racial lines, who found themselves challenged by the war’s life-changing events. Yet such assumptions about how the White population in the free states used “freedom” also can lead us astray. For a broad spectrum of the loyal citizenry of the United States, including almost all Democrats, the word could have conjured images not of ending slavery but of guaranteeing and extending their own liberty and freedom in a nation where, politically and economically, the cards were not stacked irrevocably against common people.

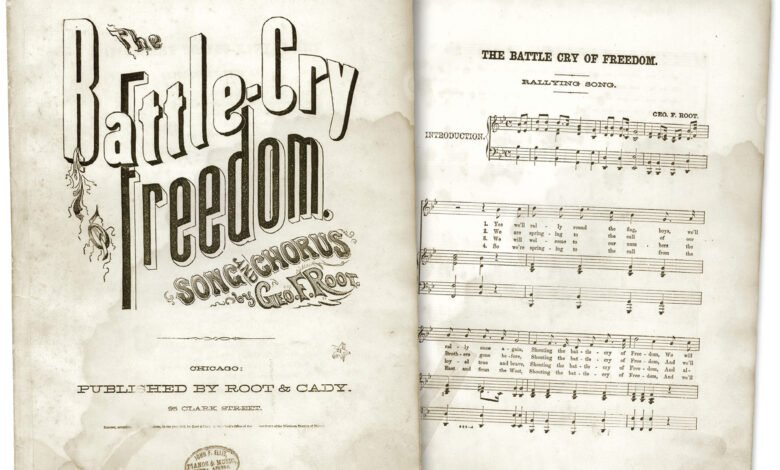

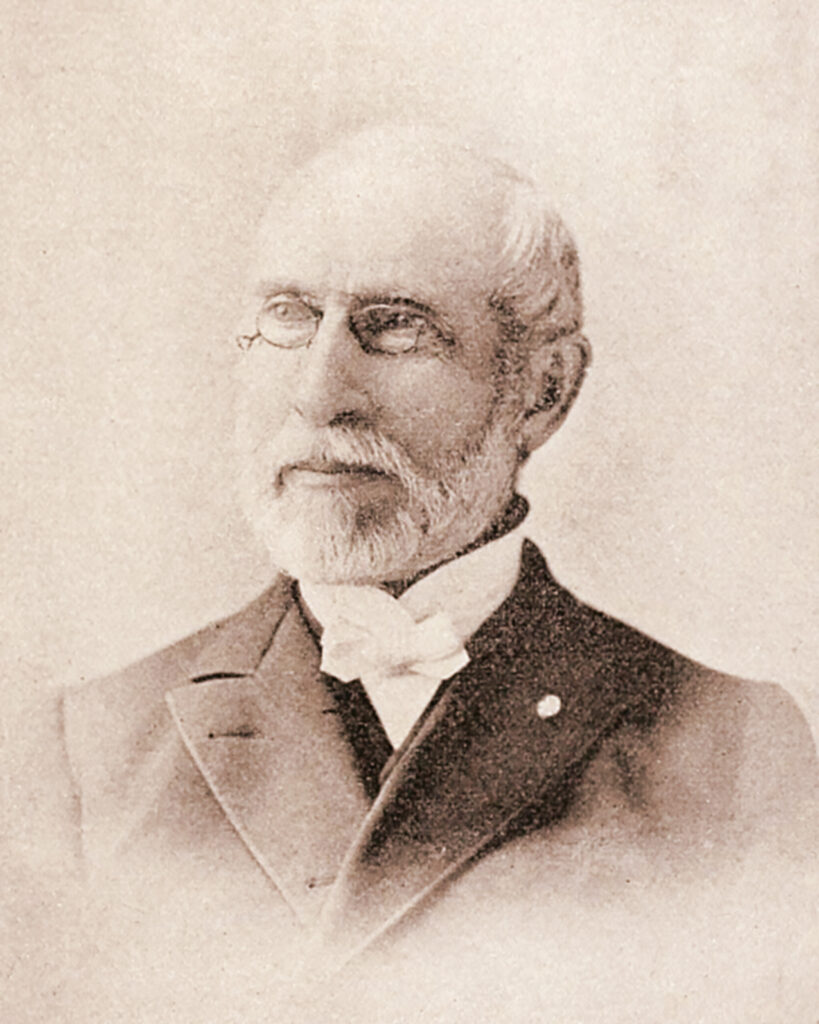

George F. Root’s song The Battle-Cry of Freedom offers an opportunity to explore this phenomenon. Among the most popular compositions for loyal soldiers and civilians, its sheet music sold more than 500,000 copies in the 19th century. Root’s lyrics not only shed light on what mattered to those who sang and listened to them, but they also demonstrate the importance of ascribing contemporary meanings to language deployed by the Civil War generation. “Freedom” is the key word in the song’s title. A reasonable conclusion might be that Root, writing in the summer of 1862, authored a call for White men to enlist and end the practice of human bondage by force of arms. After all, Congress already had outlawed slavery in the District of Columbia and the Federal territories (on April 16 and June 19, 1862, respectively), and discussion of more general emancipation grew increasingly heated inside and outside Congress.

However plausible, such an interpretation fails to account for the origins of the song and its great appeal in the United States. “I heard of President Lincoln’s second call for troops one afternoon while reclining on a lounge in my brother’s house,” Root recalled in his memoirs. “Immediately I started a song in my mind,” he continued, “words and music together: ‘Yes, we’ll rally round the flag, boys, we’ll rally once again, / Shouting the battle-cry of freedom!’” Root thought about the piece through the rest of the day and finished it the following morning. “From there the song went into the army,” he remembered with obvious pride, “and the testimony in regard to its use in the camp and on the march, and even on the field of battle, from soldiers and officers, up to generals, and even to the good President himself, made me thankful that if I could not shoulder a musket in defense of my country I could serve her in this way.”

(Courtesy of Northern Illinois University )

Emancipation almost certainly did not preoccupy Root as he composed what he termed a “rallying song.” Lincoln’s call for the governors of loyal states to supply 300,000 3-year volunteers, dated July 1, 1862, and released to the press the next day, sought to boost volunteering across the United States. National conscription lay many months in the future, as did large-scale recruitment of African Americans, so anything that might help place more White men in uniform during the summer of 1862 would assist the Lincoln administration and the war effort.

For the song’s targeted audience, “Union” provided the hook, with preservation of existing American freedom as one of the obvious benefits of vanquishing the Rebels. The chorus conveyed the principal message: “The Union forever, Hurrah, boys, Hurrah! / Down with the traitor, Up with the star; / While we rally round the flag, boys, / Rally once again, Shouting the battle-cry of Freedom.” Echoing Daniel Webster’s famous call for “Liberty and Union, now and forever,” the chorus supported the idea of a perpetual Union so dear to Lincoln and countless others.

The second verse tied prospective volunteers to White men who had enlisted earlier and suffered casualties that left military units shorthanded: “We are springing to the call / Of our brothers gone before, / Shouting the battle cry of Freedom; / And we’ll fill our vacant ranks / With a million free men more, / Shouting the battle cry of Freedom.”

The third verse invited all classes of men to step forward with a promise of rights within the Union: “We will welcome to our numbers / The loyal, true, and brave, / Shouting the battle cry of Freedom, / And although he may be poor, / Not a man shall be a slave, / Shouting the battle cry of Freedom.” The last verse spoke to a national effort uniting geographical sections: “So we’re springing to the call / From the East and from the West, / Shouting the battle cry of Freedom, / And we’ll hurl the rebel crew / From the land we love the best, / Shouting the battle cry of freedom.”

Root’s lyrics brilliantly engaged the pool of military-age White men in the loyal states—“free men” who, by taking up arms, would guarantee continued “freedom” and prevent their domination by southern slaveholders. These words appealed on the basis of a free labor vision of the American nation with a Constitution and representative form of government designed, as Abraham Lincoln put it, “to clear the paths of laudable pursuit for all—to afford all, an unfettered start, and a fair chance, in the race of life.” Many in the North believed that slaveholding oligarchs denied such a path, and thus real freedom, to non-slaveholding White people in the South, and that the Slave Power’s inordinate influence in the antebellum federal government had presented a continuing obstacle to greater expansion of political and economic opportunity.

Root translated Webster’s soaring rhetoric into a paean to Union with an infectious melody and well-crafted lyrics that spread through army camps and patriotic gatherings on the civilian front. As the war progressed, emancipation joined restoring the Union as a stated national goal, and Black men entered the army in significant numbers. Those striking changes meant that Root’s memorable song could summon thoughts of both preserving freedom long enjoyed by White Americans and expanding freedom to millions of African Americans who had suffered under the tyranny of slavery.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of Civil War Times magazine.